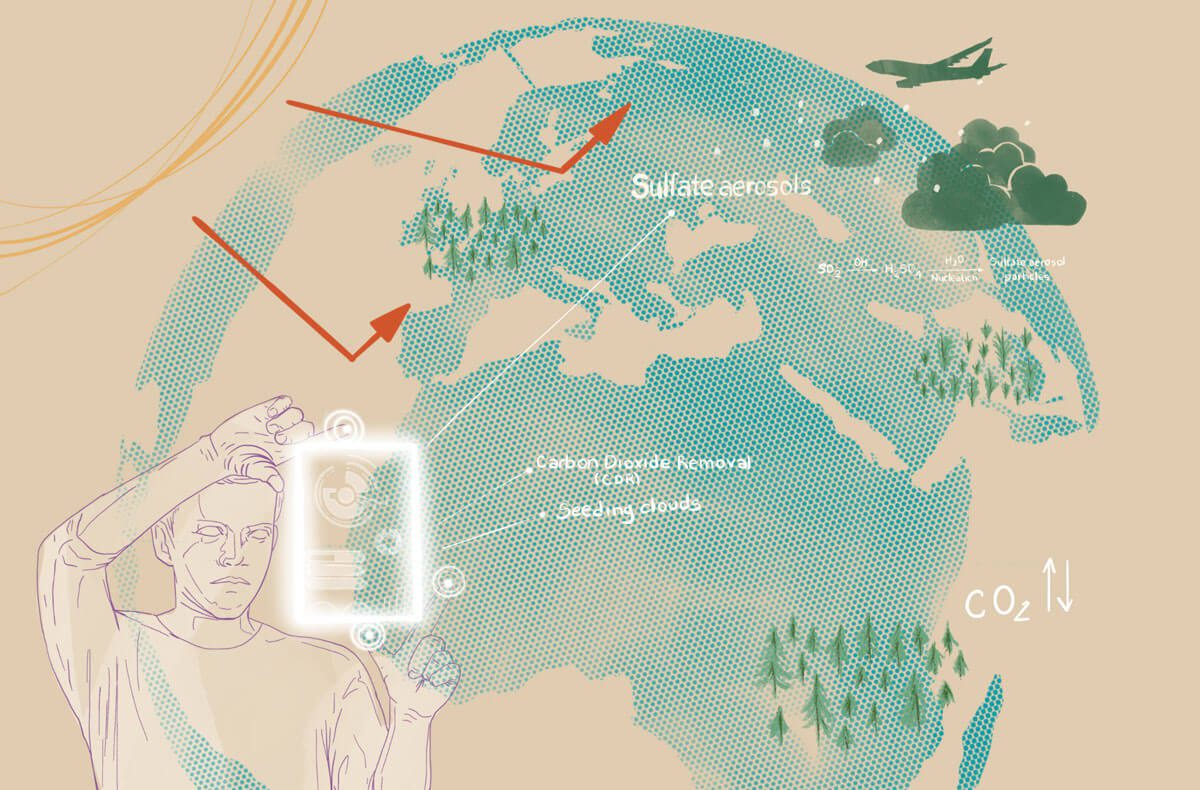

Illustration by Juliana Lagerstedt

How big a threat is geo-engineering our environment to prevent climate change? Battle lines are being drawn in the scientific community as we speak. So we posed the question to the supposed sum of all human knowledge, the controversial AI program, ChatGBT:

“In comparison to AI, geo-engineering is not as threatening,” the program spat. “AI is a rapidly-evolving technology that has the potential to transform virtually every aspect of our lives. It is also capable of making decisions and taking actions that can have profound and far-reaching implications. For this reason, many people feel that AI is a much greater threat than geo-engineering.”

Hmm. Sounds defensive. Until you realize that the nascent industries of geo-engineering, from cloud seeding to carbon storage and removal, to ocean fertilization, are all going to be heavily dependent on artificial intelligence going forward.

Like AI, whose prospects we’ve been debating for decades, with fears of an armed race of robots enslaving the human race, geo-engineering has already been let out of the box. China routinely seeds clouds to make rain. A half dozen plans to fertilize the oceans with iron to grow more plant life to remove carbon are already in the works. And more than 350 startups have raised money in the last few years to try to remove harmful carbon dioxide from the atmosphere.

One company, Making Sunsets, reportedly took it upon itself to spray chemicals into clouds last year in Mexico to deflect sunlight, before its experiment was shut down by government authorities. Just like with AI, governments won’t be able to regulate geo-engineering. Science advances, with all its unintended consequences.

Laboratory-based Covid, anyone?

In fact, the biggest threat from geo-engineering is probably geo-politics, in which countries may someday use environmental manipulation against each other, in some new form of scorched earth military tactics. That is why the scientific community is jumping all over itself to discourage any sort of man-made tinkering with the atmosphere or oceans. They are afraid we won’t be able to stop what we start.

Still, the controversy has perked up again in the last few weeks, after billionaire philanthropist George Soros hopped on board the geo-engineering bandwagon with a suggestion at the Munich Security Conference of world leaders that we experiment with spraying salt water into the clouds in the Arctic.

The idea was quickly denounced by some, while other scientists said that perhaps more research is necessary.

But no amount of political bluster will stop the relentless pursuit of tech experiments to create the solution that might indeed save the world. Perhaps shooting sulfur into the atmosphere to block the sun and create the earth-cooling effect of an erupting volcano isn’t the wisest idea at this juncture. Is the same true about nuclear fission?

Last we checked, hundreds of millions of dollars have been invested in carbon removal. The science proceeds because the world demands it. Three decades of international discussion about reducing our reliance on fossil fuels and gas have led almost nowhere. Ultimately, our economies will rely on wind and solar power, and electrified transport, but not without painful transitions, and time wasted that we do not have.

Like nuclear power and AI, geo-engineering will be part of our eventual solution—because it must. How we get there will determine the future of our species, and become the biggest question in human history. Will we find a solution that works for the world, or desperately try to blow up the coming meteor at the last minute, a la the movie Don’t Look Up?

Despite having the sum of human knowledge on the Internet at its command, somehow I don’t think ChatGBT quite has the answer yet.