“Scores of child asylum seekers kidnapped from Home Office hotel,” revealed shocking news headlines from The Guardian and The Observer on 21 January. “Dozens of asylum-seeking children have been kidnapped by gangs from a Brighton hotel run by the Home Office in a pattern apparently being repeated across the south coast, an Observer investigation can reveal,” ran the scoop by two of Fleet Street’s oldest publications.

I’m a big fan of The Guardian and its Sunday publication, The Observer, and have written for both. Generally speaking, they are reliable, authoritative, and evidence-based papers. Certainly among the best of Britain’s aggressive and news-hungry media.

Two days after the scoop, this important story about missing unaccompanied asylum-seeking children (UASCs) was followed up by a good local newspaper, The Brighton Argus. “Dozens of child asylum seekers kidnapped from Brighton and Hove hotel,” the Argus confidently told its readers. It also branded Brighton & Hove City Council “complacent and ineffective” because “dozens” of children had been “abducted.”

Cue a national pile-on. Other papers reported the story, senior MPs wrote op-eds about children being “snatched,” and van loads of TV news crews descended on Brighton. Peter Kyle, MP for Hove, warned missing children were being “coerced into crime.”

Local safeguarding authorities on the UK’s south coast were lambasted for failing to stop predatory gangs targeting vulnerable asylum seekers who’ve made dangerous “small boats” crossings over the English Channel.

It was the perfect media storm.

But there was just one problem: there was not a shred of actual evidence that organized criminals had “kidnapped” or “snatched” any UASCs.

There was evidence that asylum seekers—including many children—had been illegally trafficked from France. As New Thinking‘s recent coverage shows, Britain has managed record numbers recently.

There was also a lot of evidence that vulnerable UASCs had gone missing from a specific hotel in Brighton while awaiting a more permanent local authority care placement. The hotel—which NT won’t name to avoid revealing where vulnerable children stay—has been home to 1,600 UASCs since July 2021. Of these, 137 have been reported as missing at some point, and 76 have never been officially traced.

On the face of it, it’s a scandal. So the media coverage certainly piqued my interest.

But after making a few calls to well-placed contacts, I quickly established that many safeguarding professionals—at Brighton & Hove City Council, the police and Home Office—were less sure that missing hotel children were the victims of kidnappings or coercion. The media language around the issue, sources said, had quickly become sensationalist, inflammatory, and potentially misleading.

Nonetheless, Brighton & Hove’s Safeguarding Children Partnership (BHSCP) was under pressure to investigate. So in late January, the partnership commissioned an independent expert to assess the situation. Step forward, Chris Robson: a former police detective and safeguarding specialist. Robson spoke to all key public bodies and published his report on 28 February. It makes for interesting reading.

The former detective reports: “From the data provided, it is clear there is an ongoing issue with the number of UASC children who are going missing from a hotel in Brighton and Hove.” The ex-detective in no way underplays the worrying numbers and asks serious questions about whether UASCs should even be kept in temporary hotel accommodation.

“The scale of the issue…does give rise to significant concern,” he continues. But turning his attention to whether media reports about kidnappings from the hotel were accurate, Robson reveals: “I have been provided with no evidence that children are being ‘snatched, abducted and coerced’ by criminals.”

“The use of such highly provocative language should be carefully considered and limited to instances where there is clear evidence that such offending is taking place. The impact of such statements can undermine public confidence and lead to children being fearful of a threat that does not exist,” he adds.

Indeed, Robson’s report reveals that while Sussex Police are concerned about links between “small boat” crossings and organized crime, “of the children who have gone missing, only a small number have been found to have been exploited.”

For the most part, the missing children appear to leave the hotel in question to link up with family or friends across the UK—or to seek work if they are older. “Many are located with relatives and/or friends whilst others self-present to police after a period of time,” Robson concludes. It’s noteworthy that, of the 76 untraced children, 37 are now adults, and the remaining 39 are all now aged 16 or older.

Of course, there is no room for complacency. No public body investigating missing asylum seekers—particularly children, however close to adulthood they are—should rest easy when individuals officially remain unaccounted for. Such complacency merely invites genuine criminals willing to exploit uncertainty.

Robson’s report, for example, reveals there was a recent incident in which Sussex Police stopped a car containing suspected traffickers and two 17-year-old residents of the UASC hotel. It is possible this incident sparked the widely repeated claims about “kidnaps” or coercion. But Robson’s report states local police are not treating their ongoing investigation as a kidnapping.

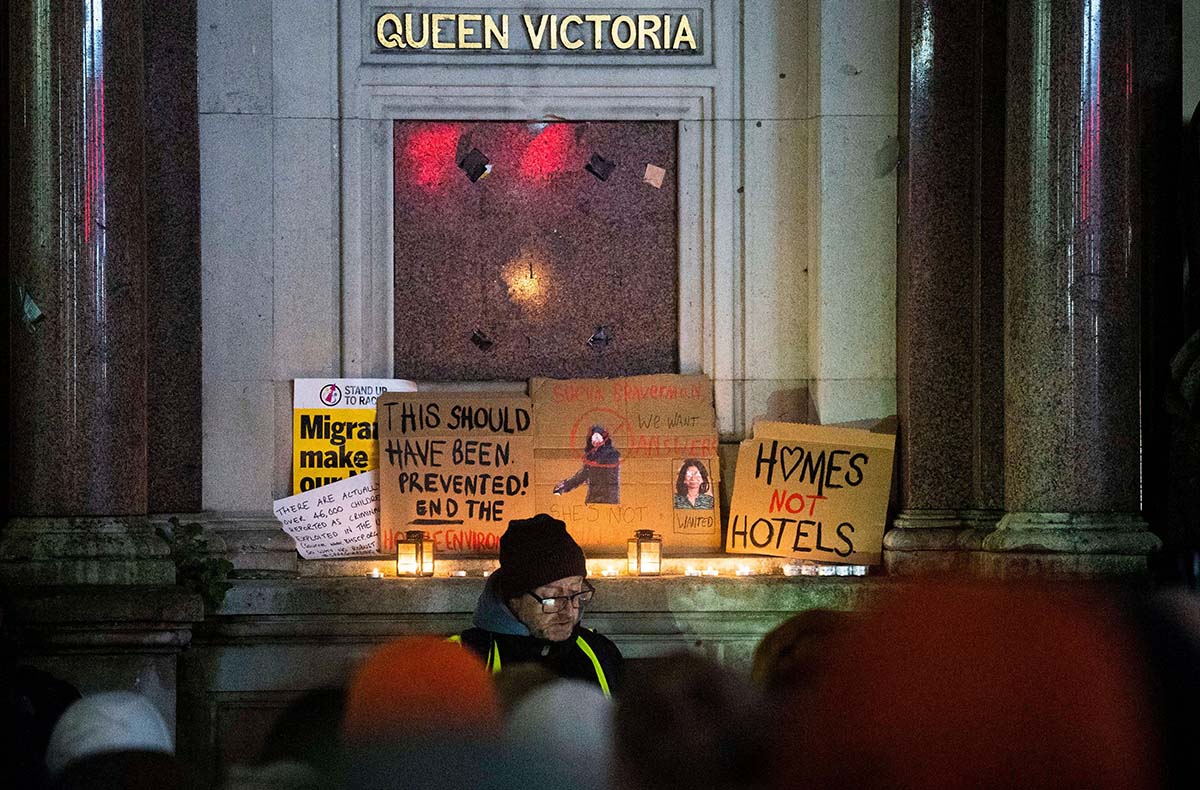

There seems little doubt that barely evidenced media coverage of goings-on in Brighton has allowed a few unhelpful myths about UASCs to develop. Myths that now need to be carefully unpicked by professionals. As the recent riot in Knowsley, Merseyside, showed: misinformation about asylum seekers can quickly escalate and create community tensions.

Unfortunately, this sort of thing happens during a media rush to “get the story” and publish headline-grabbing coverage. I’ve previously fallen foul of such reporting—which news journalist hasn’t? For that reason, I’m sympathetic towards The Guardian, The Observer, The Brighton Argus, and other media. They remain strong publications that perhaps overreached on this specific issue.

But this all acts as a sharp reminder. In these days of 24/7 news and sensationalist social media: check your facts, then check them again. It remains the basis of all solid journalism.