Most businesses don’t exist to solve social problems like generational poverty, low social mobility, crime and mass incarceration—despite the vast array of lofty mission statements out there. With a need to drive profit margins, optimizing performance is often a higher priority for leaders. Most simply want to make better decisions, faster. It’s a worthy aim, despite the natural tension that can exist between better and faster. Often, working with a socially and culturally homogeneous team can appear to support this outcome, but what’s lost in the comfort of so much common ground? Does the best thinking really emerge, let alone prevail?

According to MIT Sloan School professor Evan Apfelbaum, not so much. In an interview with Martha E. Mangelsdorf for MIT Sloan Management Review, he highlights the flaws in homogenous culture and points to the power of a diverse work environment to produce more rigorous decision-making with fewer mistakes. Why? People were less comfortable in the diverse environment and less likely to conform, less likely to adapt the ideas of others without scrutiny and more willing to examine alternative perspectives. The presence of a perceived outsider can heighten our senses. In primitive times, an outsider represented a threat. In today’s world, the threat might take the shape of a whistleblower.

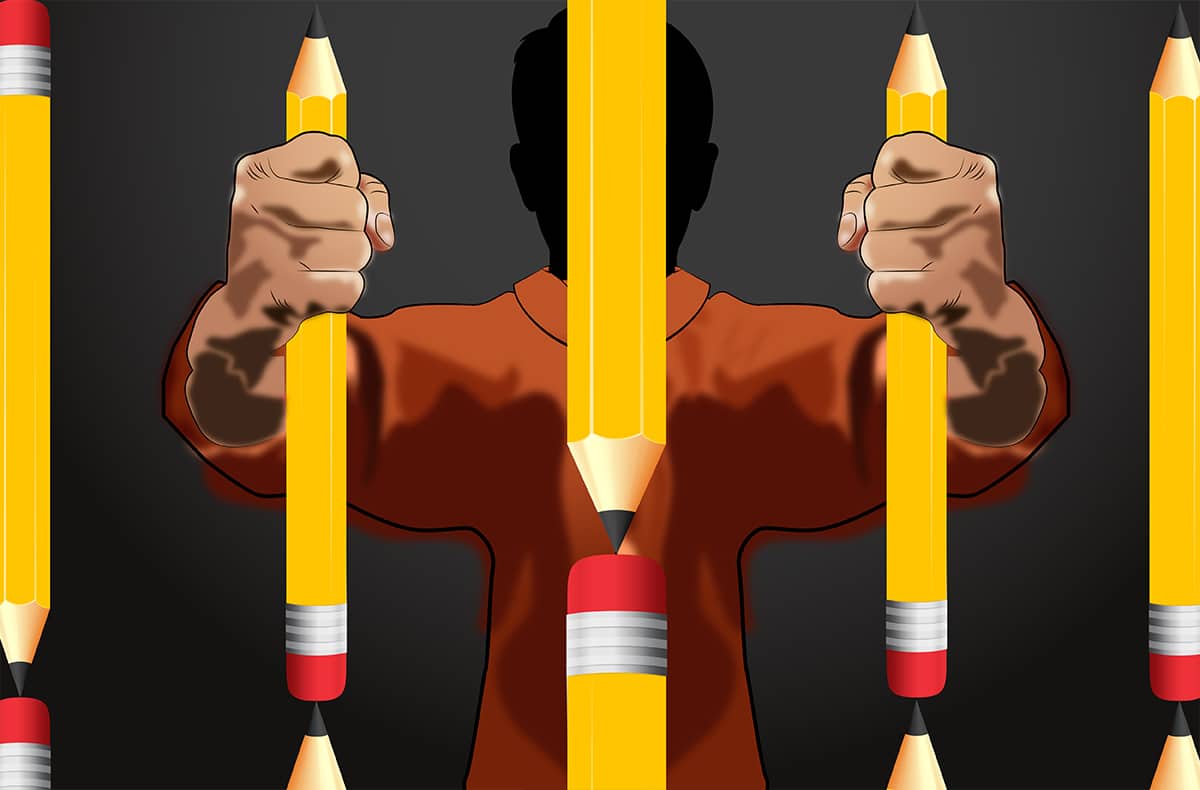

So, diversity is good—but what does diverse really mean? I can’t ignore the fact that most people’s version of diversity is quite limited. This point has been driven home time and time again as I have spent my early career in some fairly homogeneous corporate environments and my later years in the non-profit sector co-leading an organization, Inside Circle, which serves a highly diverse and disenfranchised population: the incarcerated and formerly incarcerated. Often, and rightfully so, companies look to balance their teams based on race, ethnicity, and gender, but even teams that represent all of these groups can remain homogenous in other ways and succumb to dreaded psychological fallacies like group think. One less frequently applied lens to explore when asking the question, “Is my team actually diverse?” is social class origin. More often than we realize, teams share a high degree of implicit cultural capital that eases their way socially. Accrued in the classrooms and summer camps of privileged communities and the dorms at top tier universities, most teams share a common language, set of beliefs, and references that provide unseen advantages.

An individual’s social class of origin and in many cases these days, criminal record, can represent the greatest disadvantage when seeking a seat at the table. Recent research from Paul Ingram and Jean Oh of Columbia Business School, found that US workers from lower social-class origins, possessing education inequality and even more challenging cultural capital deficits, are 32% less likely to become managers than are people from higher origins. Surprisingly, this disadvantage is even greater than that experienced by women compared with men (27%) or Blacks compared with whites (25%). In fact, those from lower social-class origins seem more likely to be incarcerated—forming the ranks of the roughly 70 million or more people with a criminal record in this country—than to hold a board seat.

It’s not ground-breaking news that poverty and crime walk hand-in-hand but let’s not forget it, folks. A 2018 report by the Brookings Institution found that boys born into households in the bottom 10% of earners were 20 times more likely to be in prison on a given day in their early 30s than children born into the top 10%—the group mostly likely to be ideating on Zoom. And once that conviction is in place, good luck finding any job—let alone an influential one. Formerly incarcerated people experienced a 27% unemployment rate in 2018, the highest rate in our nation’s history and research published by University of Michigan shows that minor felony records have large negative effects on employer callbacks in response to job applications. But again, we really didn’t need a study to tell us this.

According to the Prison Policy Initiative: “The American prison system is bursting at the seams with people who have been shut out of the economy and who had neither a quality education nor access to good job…This gap in income was not solely the product of the well-documented disproportionate incarceration of Blacks and Hispanics, who generally earn less than Whites.…incarcerated people in all gender, race, and ethnicity groups earned substantially less prior to their incarceration than their non-incarcerated counterparts of similar ages.”

Most often we calculate the cost of this troubling dynamic by examining the costs of property loss, adjudication, and incarceration, but we never really look at what we are missing when millions of human beings—their voices, perspectives, talents—are absent from influential decision making.

Now, we already know that social mobility has a benefit beyond the value of social justice. I see this every day in my work. When people are matched with jobs that match their talents—no longer limited by origin—productivity goes up, GDP goes up, and crime goes down. But where does this leave us? There is outstanding work being done in this arena, organizations like The Second Chance Business Coalition and many employment social enterprises are leading the way, but the fact remains that professional job opportunities for most formerly incarcerated and other groups lacking the cultural capital to mix in the corporate world are few and far between. We need a massive effort to confront this dynamic and reap the benefits of truly diverse teams.

One San Francisco-based consultancy, The Trium Group, is joining the fight by helping formerly incarcerated people who transformed their lives in prison support groups get professional coaching training. They are building coaches with a unique perspective who can lend insight in unexpected ways because they have been to hell and back and demonstrate that change is possible in ANY circumstance. Who wants a coach who has never come face-to-face with adversity? This is inspiring, folks and might be just what we need to support fresh thinking. And sure, it might slow us down a bit, but sometimes we have to slow down to speed up.

Note: Analysis of Bureau of Justice Statistics data by The Sentencing Project.