A lot of what I’ve been seeing online in recent days reminds me of this Austin Powers quote, “There are only two things I can’t stand in this world: People who are intolerant of other people’s cultures, and the Dutch.”

Since Putin’s invasion of Ukraine, Russophobia is on the rise again. I see countless tweets saying “the Russians” are all behind it, even though I have yet to speak to a single Russian person who approves of this war. Artists like Alexander Malofeev are having their shows canceled while being pressured to publicly condemn the war, even though doing so is punishable by up to 15 years in prison in Russia. And restaurants like the Russian Samovar—a Manhattan stalwart that has a now unfortunate name—have been subjected to hate crimes.

I spoke with Vlada von Shats, the restaurant’s owner, about it recently, who said the restaurant had been receiving bad reviews from people telling them to “stop the war,” canceled reservations, and hate mail and phone calls calling them “Nazis.”

“The restaurant was basically empty for two weeks,” she told me recently, in person. As if they have anything to do with it. As if this will in any way help people suffering in Ukraine. “Of course we’re against the war,” she said. “Over half of our staff is Ukrainian.”

She immediately sprang into action, doing dozens of interviews for large and small outlets. It worked. At our interview, she showed me several handwritten letters from people all over the country, sending checks and messages of support. One of them said they only make $12,000 a year and still sent $100. “I don’t know if I even feel comfortable cashing that check,” she said.

For all of the destruction, prejudice, and hate going on in the world, it feels uplifting to see a gesture of human kindness. “I get about 300 phone calls of support these days, maybe 30 in which they tell us to die,” she said, smoking a cigarette, with a regal cavalierness that I found both inspiring and enviable.

“We’ve dealt with this before,” she said, with a weary sigh. “In the ‘80s, they called us ‘commies.’”

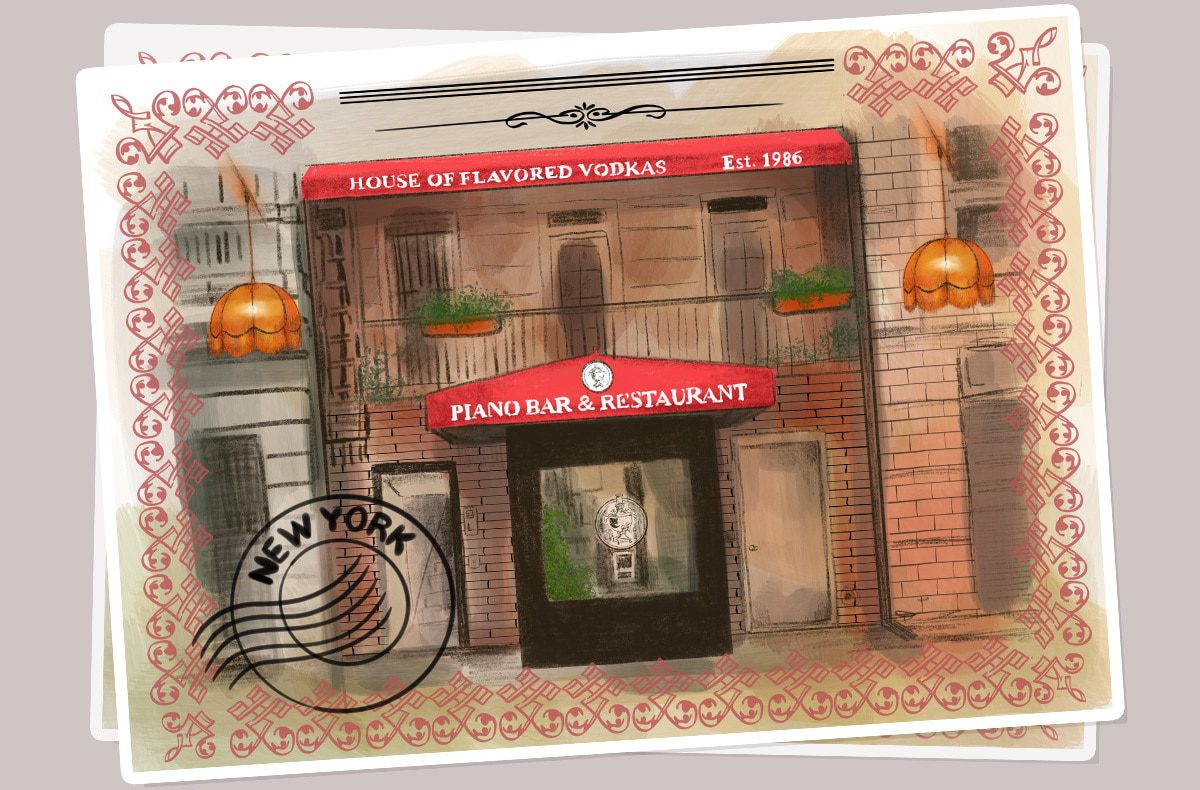

The Russian Samovar is a New York institution that was founded in 1986 by Roman Kaplan, the world famous dancer Miklhail Baryshnikov, and the Nobel Prize-winning poet Joseph Brodsky. I have always loved it, with its delicious food, its baby grand piano, and its red-tassel lamps hanging over white tablecloth tables—which make you feel like you are in the elegant dining room of a 1920s train heading somewhere incredible.

It is also personally special to me. My mother, a folk singer, used to work here. I used to fall asleep at one of the shawl-draped tables near the piano, doing my math homework, while she belted out songs from a country she had left but whose music she had kept.

That was always the heart and soul of the Samovar. It was a place where emigrés who had fled the political persecution of the Soviet Union could come to enjoy what they had always loved about their homeland—the culture, the food. It was a place that understood that food unites people, but so does music.

“I’ve worked at the Samovar since the mid-2000s,” Sergei Pobedisnki, one of the musicians who performs at their weekly shows on Friday and Saturday nights—and a close family friend and neighbor—told me. “This place has been like an island for me, one which prevents me from ever sinking to the bottom.”

His wife, Lyudmila, is Ukrainian, and, like most people, he was in shock and horror at the events that unfolded. “We immediately called her relatives in Kyiv,” he said. “It’s horrible. It’s impossible to fathom how this can even happen in the 21st century. There’s no logic to this war. And Ukrainians will never forget it.”

I was there on Sunday, March 12th, for a fundraising event for Ukrainian staff members. The evening featured an outstanding performance of Ukrainian music and dance. One of the dancers blew the back off of a chair. That’s how you know it’s good.

The other dancer, also a close family friend, came over to give me the standard compliment: “You look so skinny! Have you lost weight?” I’ve been “losing weight” since I was 15. I turn to my friend to joke that it’s such a Russian thing to say, then hesitate. I don’t know if she’s Russian or not. She might be Ukrainian. What do I use instead? Slavic? Eastern European? It used to not matter. Now, it means everything.

I tell my friend that it’s funny that this place was founded by emigrés and that now it will have a whole new generation of people fleeing Russia. As a Russian citizen, I am subject to Russian law, which means I’m not sure when, if ever, I’ll be able to visit my homeland again. “I wonder if this is how our parents felt, leaving Russia, taking what they loved about it with them, never knowing if they could ever return,” I say, tearing up. She nods.

A Ukrainian song comes on that I love, one which requires mimicking being on the back of a horse. I fervently sing along. My friend is the type of kind, compassionate human being who feels guilty having a good time while people in the world are suffering. I turn to her and say, “People in Ukraine won’t be any better or worse off if you forget your troubles for a couple of hours.” She smiles. We eat, we drink, we dance.