When a politician is in trouble, they invent demons to vilify.

So, long before she was forced to resign on 20 October, you could have bet your expensive UK mortgage on the idea that Britain’s prime minister, Liz Truss, was in so much trouble she wouldn’t reach the next General Election.

As it transpired, trust in Truss collapsed even more dramatically and she served as PM for just 44 days: the shortest tenure ever in Britain. Truss took office on 6 September. Yet, when she addressed a chaotic Conservative Party conference on 5 October, her reputation was already so low—and her decision-making so ridiculed—that she randomly attacked her many detractors as an ‘anti-growth coalition’ including (but not limited to):

- Those opposing economic growth

- “Remainers” who opposed Brexit (48% of Brits)

- Large chunks of the media

- Most opposition political parties

These people, Truss claimed, were the real obstacle to Britain’s progress, as opposed to a slate of indicators that the UK has bigger fish to fry.

The list of parties Truss blamed for her calamitous first month was such a paranoia fuelled Trumpian catalogue of imagined enemies that it was evident neither she, nor her inexperienced advisers, had thought things through. If they had, they’d have realised the PM declared war on more than half of Britain’s population. Not an election-winning tactic.

And therein lay Truss’ problem. She was not elected PM by the general public. So there was no evidence she appealed to, or understood the needs of, a critical mass of voters. By taking over from law-breaking haystack Boris Johnson through an internal Conservative vote, Truss was chosen by just 81,000 party members. That’s significantly fewer people than watch the England football team at Wembley Stadium in “anti-growth” North London!

The system used to select mid-term PMs requires reform. But that’s a discussion for another day. Back to the catastrophe…

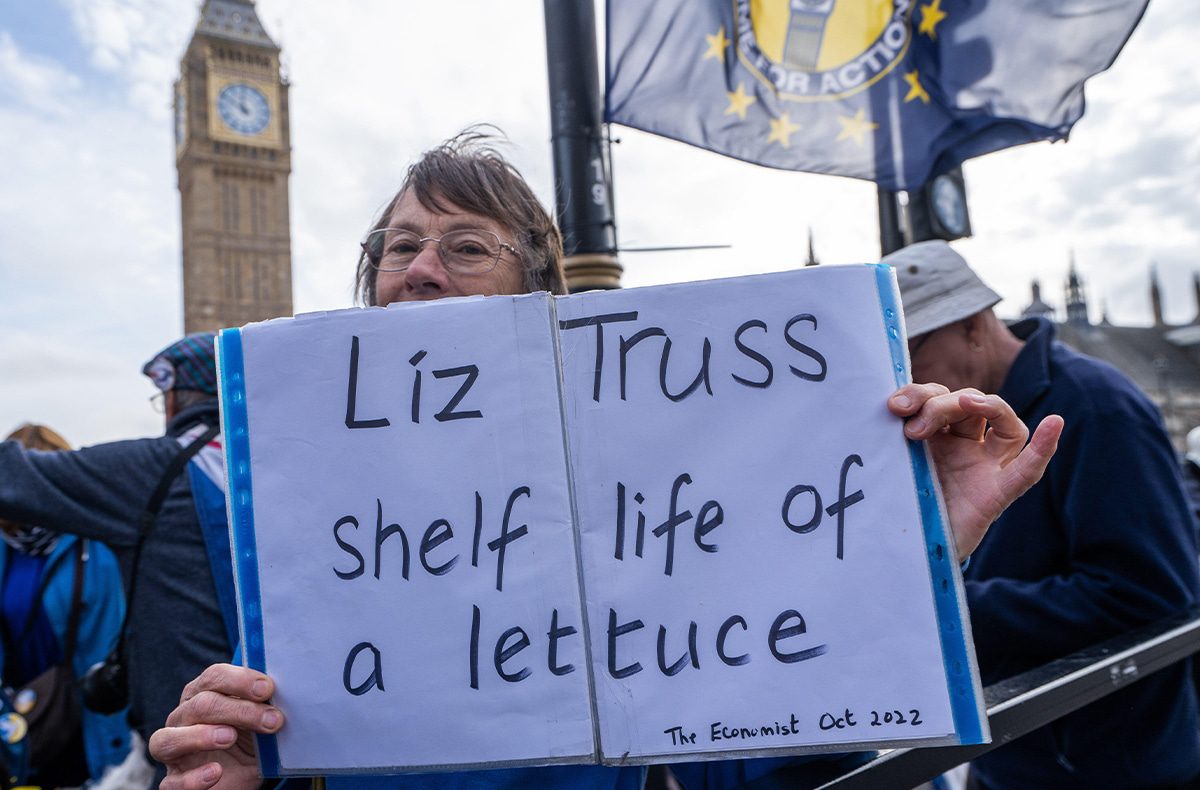

Truss oversaw the worst start to a political era since Mexico’s Pedro Lascurain resigned after 45 minutes in 1913. She led the Conservatives, who traditionally seek to “roll back the frontiers of the state” and lower taxes, so badly that even The Economist magazine—an influential champion of economic liberalism—declared her government epitomised ‘how not to run a country’ and compared the chaos to post-war Italy (69 governments lasting 1.11 years on average!).

It was almost impossible to imagine a leadership could implode so quickly. Truss inherited a Britain on its knees following a disastrous and divisive Brexit, COVID-19, vulnerability to soaring energy prices and inflation, and Johnson’s self-inflicted demise. The incoming PM only had to stand up to appear relatively competent.

But instead, Truss fell over. Repeatedly.

Admittedly, she was hindered by her hapless first chancellor, Kwasi Kwarteng. He was quickly dubbed ‘Kami-Kwasi’ after economic gaffes so consequential one wonders if he actively tried to crash the economy. After calling an early Budget, Truss and Kwarteng—both on the Right of the Conservative Party—announced swingeing and uncosted tax cuts they believed would boost the economy. These included scrapping the 45p income tax rate for Britain’s highest earners and removing a cap on bankers’ bonuses: policies interpreted as Conservative leaders looking after their wealthy donors.

Not so, Truss argued, the new policies reflected her laser-like focus on wider economic growth.

But global markets and investors disagreed. They saw a lack of financial credibility and worried that, by cutting government revenues (taxes), Britain could not cover its borrowing. What followed was a destabilising loss of confidence in—as one on the sceptered isle might put it—skint Britain so rapid we wondered whether Usain Bolt had emerged from retirement. Around $161bn was wiped from the UK economy. The US dollar achieved near-parity with the weakening pound, and the Bank of England was forced to buy UK gilts and hike interest rates —ending borrowing (i.e., mortgage) costs soaring.

All of this was the direct result of Truss and Kwarteng’s first dabble with grown-up economics. It was an unmitigated disaster. So when the Conservatives gathered in Birmingham for their annual shindig a week later, the knives were out. Truss and Kwarteng responded with an embarrassing U-turn over the controversial 45p tax rate. But the PM immediately undermined this volte-face by stating that she remained committed to the policy in principle: indicating she’d like to U-turn on her U-turn!

Sensing that opposition to her leadership was snowballing among sensible Conservatives, Truss also threw her chancellor under the bus by stating that Kwarteng unilaterally implemented the unpopular tax cut. While UK citizens grimaced at this mind-blowing incompetence, the Conservative Party descended into open warfare. Former Cabinet ministers warned they would lead further rebellions against proposed welfare cuts, while supporters of Truss and Kwarteng claimed they were victims of an internal “coup.”

At the conference, Kwarteng defended his hastily revised policies with all the confidence of a dog running away from the smell of its own farts. (hat-tip to comedian Stewart Lee for that joke!) Then Truss delivered that speech: demonising a huge chunk of voters and attempting to elicit hatred for invented opponents.

It placated nobody. Britain’s allies, including US president Joe Biden, openly criticised Trussonomics. In a last-ditch attempt to save herself, Truss sacked Kwarteng. But to her dismay, his replacement as chancellor, the moderate Jeremy Hunt, and his economic orthodoxy were forced upon Truss by powerful Conservatives concerned the wider UK economy would collapse.

Hunt quickly repealed most of Truss’ experimental—and disastrous—economic programme. He also announced deep public spending cuts to cover shortfalls caused by international market mayhem. But Hunt’s changes served only to isolate Truss. She was no longer in control of her government. Elected on a failed policy agenda she could no longer deliver, Truss was a “zombie” PM. Her dream was over and, amid fury among her Cabinet and backbench MPs, she stood down. Since ex-PM David Cameron called the unnecessary Brexit vote in 2015, Britain has entered a chaotic downward spiral of self-inflicted catastrophe and social divorce.

Let’s hope the next PM—“Britaly’s” fifth in six years—can reverse that.