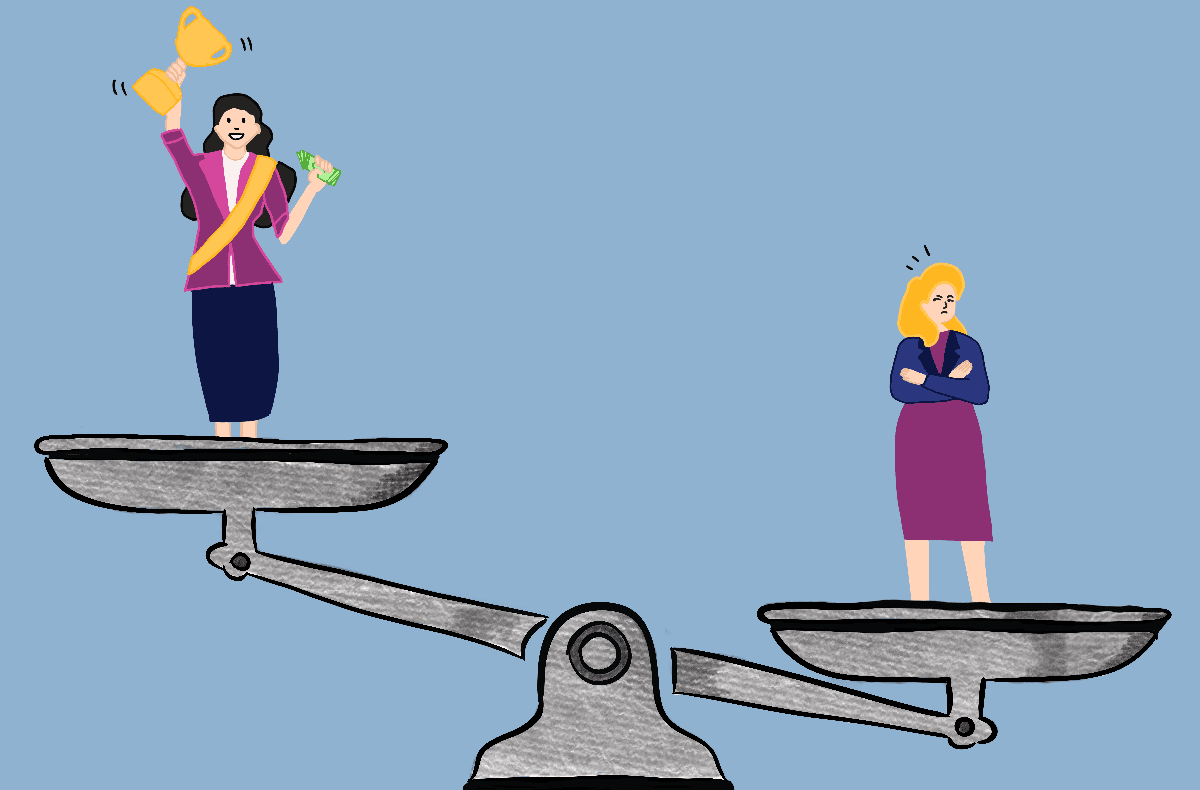

In her fabulous article on the harmful practice of comparisonitis, Jemima Atar explained the difference between a helpful use of comparison and its destructive cousin, where we find ourselves in a shame spiral after obsessing over another person’s achievements.

Unless you’re a Buddhist monk who’s attained nirvana, you’ve probably experienced your own bout of comparisonitis. Even the most well-adjusted adults are bound to have early memories from childhood of feeling like a failure when comparing themselves to that star classmate—the one who aced the spelling bee, was picked first for every team during gym class, or had the coolest, most expensive toys. “Thou shalt not envy” didn’t make it to the top ten commandments because it’s easy to avoid. In many ways, it’s one of the easiest things to do in the world.

Comparison is a natural human impulse. We make sense of the world through comparisons. It’s how we make decisions and measure progress. But as Jemima noted, when comparing yourself to others, there’s a difference between a healthy, productive practice and a spiraling, self-flagellating one. While all of us lovely, flawed individuals fall prey to this practice, I’d posit that it’s even more pronounced by gender and profession. I’m speaking in particular about cutthroat careers that are characterized by the spirit of scarcity and competition, in which women tend to have way more competition for fewer spots. Namely: the entertainment industry.

As Jemima explained, comparisonitis is bred from a scarcity mindset, and when you’re a performer who routinely waits in a room of 20 other women who look exactly like you, all vying for the one paid spot in a laundry detergent commercial, well, it’s hard to feel like success is abundant. (I could write a thousand articles about the brokenness of the entertainment industry, which only in the past decade got the memo that women’s stories are indeed, worth telling to the wider world, and that you don’t have to have a total sausage fest to get butts in seats, but for now, I’ll just allow myself a truncated rant.)

There is a wild number of talented women in the world, and we are taught literally starting in elementary school that we’ll have to be cutthroat to succeed, because most of the written material out there for school productions strongly favors male casts. This is especially true of traditional musicals with huge choruses. I can’t even describe the rage of high school Nikki in performing arts, debating which big musical our high school would produce. Time and time again, old classics like Carousel or Camelot would require gobs of male talent our high school simply didn’t have with slim pickings for the ladies: so you’d get a first-time acting male sophomore in a supporting lead, while our oodles of All-State Chorus-qualifying female singers were relegated to understudy and minor speaking roles. (What, me, bitter?)

High school productions are one thing, but the professional industry of entertainment is not all that different. Even with recent advancements in Hollywood production featuring a greater diversity of stories, there’s still countless tales of men “failing upward”—the hot guy delivering pizza in LA who becomes a movie star—while every woman you see grace the stage or screen has clawed her way to that success. So again: it’s not surprising that, generally speaking, women in entertainment often feel pitted against one another by default. In fact, I’d say it’s pretty much expected—it’s even a celebrated tradition; see: All About Eve. And that sucks. (Though Bette Davis being deliciously bitchy is always a delight.)

Once, in my earlier days, I had a comedic viral video that hit big. I’d been self-producing comedy for years, but this one just landed right in the zeitgeist, and suddenly I was getting the praise and attention I’d longed for after years of dwelling in obscurity. My college alumni magazine reached out to interview me, which was super cool—until we got to one question in particular. Another Princeton alumni, Ellie Kemper, was blasting into comic stardom with The Office and Bridesmaids. Even in college, she was a brilliant comic performer: she was a senior when I was a freshman, and when we did a scene together in an acting class, I felt like I was acting opposite a total star, even then. I had always admired her natural comedic brilliance—I can think of no one more deserving of success than her. The interviewer brought Ellie up as another “funny alumni,” and, commenting on her success, he then asked “are you jealous?”

My draw dropped. Why, because there’s only one funny woman per university allowed? I was galled. I cannot imagine anyone asking this question of a male performer. And while sure, it would be easy to be jealous of her success, I’m happy to say I wasn’t. But wow. Everyone expected me to be. And again: that sucks.

But it doesn’t have to be that way. Even when you’re in competition, you can resist the pull of comparisonitis, reminding yourself that each person is on their own journey. And even if there is still a scarcity of female-empowering roles along your dream career path, the solution is not to cut each other down, but to lift each other up. The more women who succeed professionally in male-dominated fields—whether that be in Hollywood, Washington D.C., or Silicon Valley—the better it is for all of us. It clears the way just a little bit more and opens up new possibilities.

So next time you find yourself in a spiral of comparisonitis, switch your perspective: see it as inspiration. “If she can do it, so can I.” In a scarcity mindset, success is a coveted seat in a small lifeboat you’re scrambling over others to reach; but in a mindset of abundance, success is the rising tide: it can lift all our individual ships.

As 2023 progresses, I’ll keep aiming for my own success, but what I really hope is that we’ll all succeed, together.