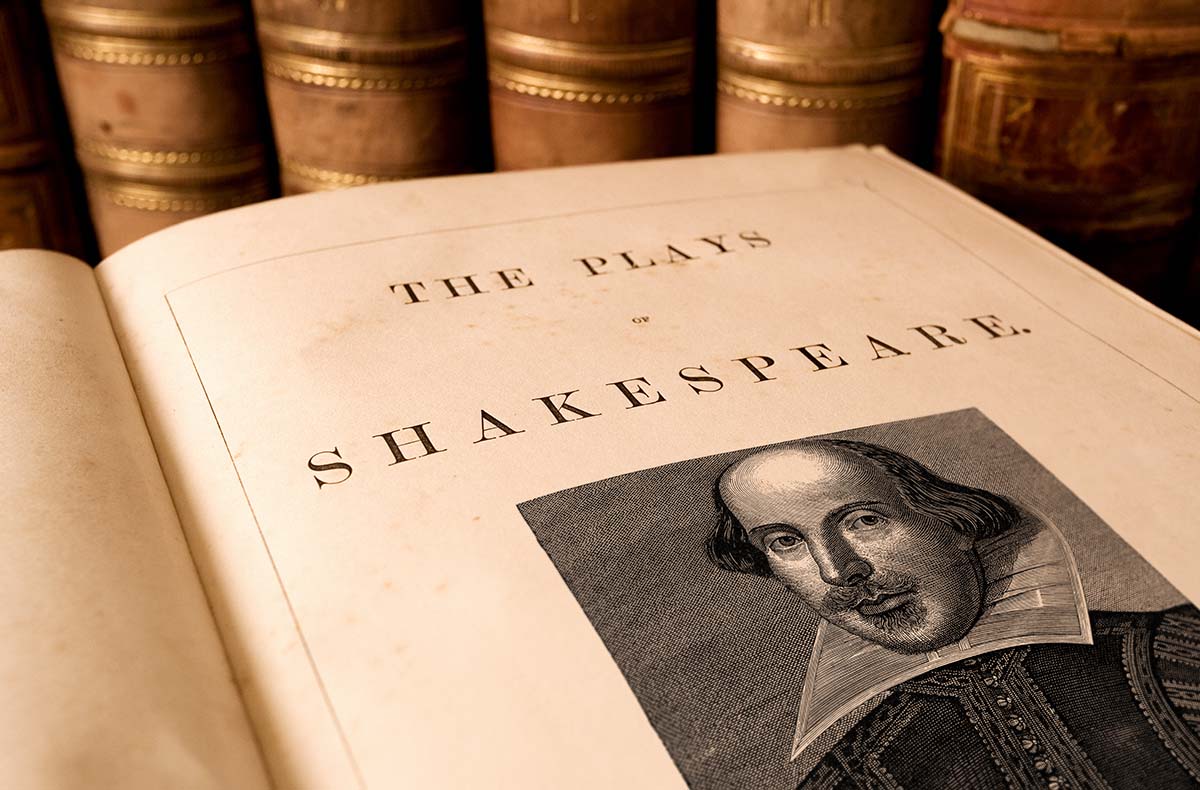

Recently, Mark Conrad’s insightful article, “All That Glisters Isn’t Gold” raised a question amongst New Thinking’s virtual ranks: what’s “glisters”? Isn’t it “glitters”? Our savvy EIC quickly noted that the original Shakespearean turn of phrase from The Merchant of Venice is, indeed, “All that glisters isn’t gold”—we just tend to adapt the word to our more 21st century version in everyday speech.

I am deeply ashamed to admit, I didn’t know that “glister” fact, although I absolutely should have—the theatre police are going to come burn up my acting M.F.A. (JK, it’s a self-destructing graduate degree!)

Like my drama nerd cohorts, I’m a big Bard fan (the playwright, not the liberal arts college—but that one’s cool, too.) Not only did he create incredible, iconic characters and timeless dramas, his linguistic contributions are astounding. He invented countless turns of phrase that we still use, from “wearing your heart on your sleeve” and “break the ice” to “elbow room.” We even have him to thank for the O.G. “C U next Tuesday”/Charisma Uniqueness Nerve and Talent joke via Malvolio in Twelfth Night, when he comments, “By my life, this is my lady’s hand. These be her very C’s, her U’s and her T’s.”

Additionally, it’s estimated that Shakespeare added an odd 1,700 words to the English language—many of which we still use today. Apparently, we have him to thank for “perusal,” which, it would dishearten Shakespeare’s to know, is often misused as “skimming” a piece of writing, the opposite of its actual meaning of reading it closely. (He also invented “dishearten.” See what I did there?)

This got me thinking: how many other iconic Shakespearean phrases are out there getting absolutely marred, if not by Baz Luhrman—whose R&J Roger Ebert called a “grand but doomed gesture” that “will dismay any lover of Shakespeare”—then just by general public misuse?

There are a few popular Bard-botches I happen to know from my Shakespearean perusal (close reading—I did mean it here). The play about everyone’s fav pontificator, Hamlet, is pretty damn quotable, but a few of the chestnuts folks jump to aren’t authentic. For starters, “Alas, poor Yorick,” isn’t followed by “I knew him well,” but by “I knew him, Horatio.” And rather than “Methinks the lady doth protest too much,” it’s actually “The lady doth protest too much, methinks.” I, too, knew these misquotes from, well, living in the world and being a human, before I dug into the text in earnest. Realizing these were incorrect was bewildering. “Wait… really? But… everyone says it that way!”

These nearly universal misquotations aren’t unique to Shakespeare: just think of Star Wars, and how everyone thinks Darth Vader said “Luke, I am your father” (he didn’t) or how scores of American Millenial kids remember the Berenstein Bears, rather than Berenstain Bears. (I was raised on these, while I could vividly retell you about the lie Brother Bear tells about an exotic bird breaking a vase instead of his soccer ball in The Berenstain Bears and the Truth, I 100% would have said it was “Berenstein”.)

Likely our collective misrememberings—which could actually be attributed to something called the Mandela Effect—are more a result of some kind of social instinct, rather than us deciding as a group that we can do better than Shakespeare. That I’ll leave up to a monkey with a typewriter and an infinite amount of time.

Returning to the original quote that inspired this musing, after citing glister’s Shakespearean origins, our EIC also mentioned that she “appreciates that Smash Mouth uses the other spelling.” A quick Google search for “all that glitters” not only leads to the lyrics of that late nineties hit “All Star,” but also to those of Led Zepplin’s “Stairway to Heaven.” Even more randomly, in a very obscure early 80s cartoon moment, Google’s auto fill suggested “All That Glitters Isn’t Smurf”. This raises another valid point: as much as it’s nice to “get it right” when it comes to quoting a treasured source, precision is not the way organic communication works. As something that springs from flawed human beings, each with their own conceptions and experiences, language is always changing, shifting, and getting recontextualized—whether it’s on purpose or not. That’s part of its beauty, not its flaw. So in my view, we’ve got to celebrate the world as the big, beautiful intertextual fiesta that it is.

In the end, whether botching, remixing, or accidentally quoting Shakespeare, so long as we are speaking and writing English, the Bard is always going to be present in our language in some way, whether we know it or not. So it couldn’t hurt to brush up on his works every now and then.