As a youth in the late 1980s, I studied US, UK, and Russian politics—or “Soviet politics” as it then still briefly was. I learned about the “separation of powers,” the “unwritten constitution” and “the proceedings of the Supreme Soviet” and more.

I took my old Uni books to the dump last week—recycling, I hasten to add—but I’m not sure they’ll find a home. They were hopelessly out of date.

Or were they…?

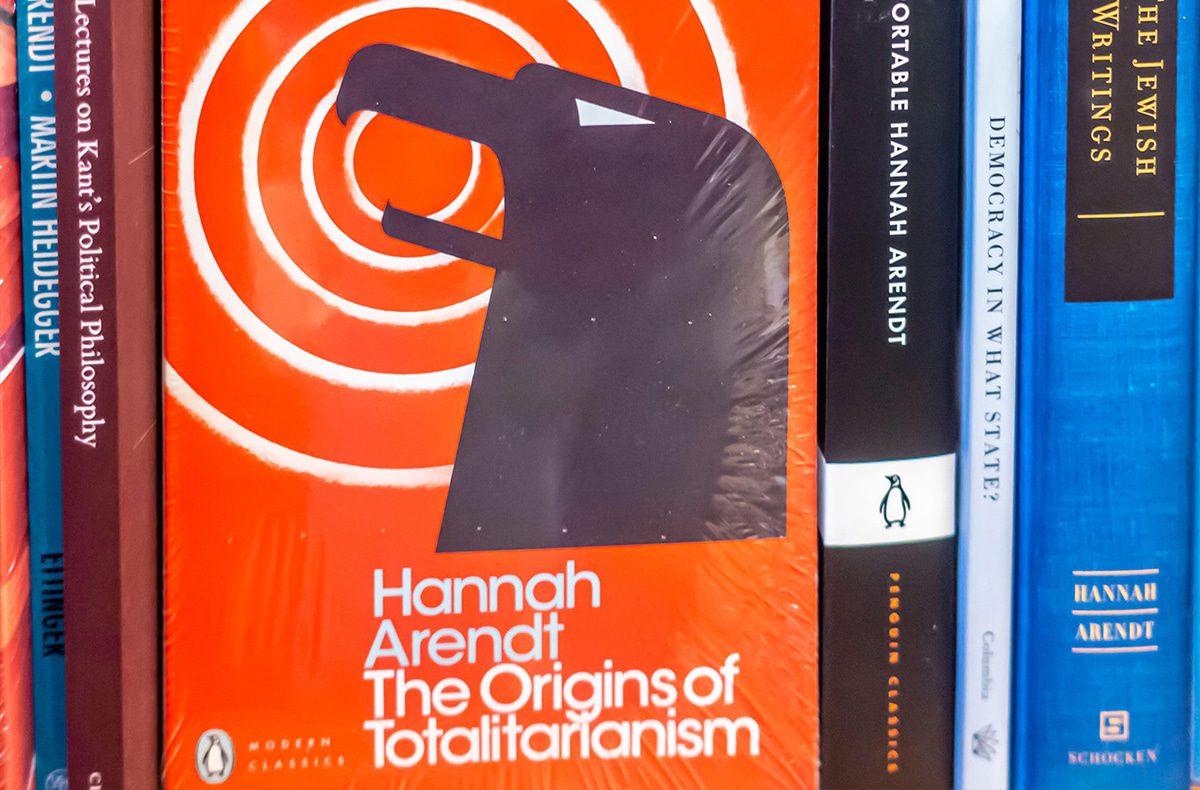

Given events in the last two years in the US, the UK, Europe, and Russia, the risk of authoritarian rule is back as never before in my adult life. So it’s well worth rereading the words of one of the 20th century’s finest minds, Hannah Arendt, on the distinctive features of totalitarian rule.

There are a number of guiding principles, which I’ve shortened and lightly edited here for ease of reading:

“Totalitarian rule has to incorporate significant elements of what preceded it, but to survive the regime must ceaselessly ensure that none of its progeny stabilise into any organised form. Whereas leaders of most organisations rely on basically stable hierarchy for their power, the totalitarian leader must continually transform their organisation—the better to control it.

As a result, governance by diktat replaces the solidity of law; personnel are constantly replaced or reshuffled; offices are endlessly duplicated to monitor one another. The only thing that everyone beneath the leader shares is submission to their mercurial and ultimately inscrutable will, an obedience cemented by rituals of idolatry that sharply demarcate insiders from outsiders.

And while no one is exempt from the leader’s domination, the highest echelon shares with him a distinctive kind of solidarity. This is based not on the propaganda intended for the rank and file, for which the movement’s elite displays a cynical disregard, but rather on a sense of ‘human omnipotence’: the belief that everything is permitted.”

Arendt had seen it in the 1930s and 40s. When I read her words around the time of the fall of the Berlin Wall, I thought them just an interesting history lesson—how wrong can you be. The US, Russia, EU, and UK (to name but four) currently wrestle with a mix of opposing—and embodying—various of these traits, depending on who you talk to.

In that context, talking about the world of work seems a bit trivial. But the first time I actually noticed Hannah Arendt’s words in action wasn’t in a nation state or bloc, but working in an organisation where the “cult of the leader” got out of hand. The truth is that these principles apply equally well to dominating a workforce as dominating a people.

What to do? Ultimately charismatic leaders can potentially overpower anything and everyone—and persuade everyone that right is wrong (remember Enron and Lehman Bros?). So what’s the best defence? Quite simply: institutions, rules, due process, principles, and the courage of individuals who stand up and defend them.

The last few years have sometimes felt like a slide into the abyss; but in the last few weeks at the national and international level, we have also seen several exceptionally brave women and men stand up for institutions, due process, and the rule of law. On a smaller scale, people in many organisations will be wrestling their demons today, tomorrow, and the next day about whether to stand up and be counted.

Hannah Arendt shows you what happens if you don’t.