There’s a bumper sticker, perhaps you’ve seen it, that reads, “Drum Machines Have No Soul.”

The first time I read this bold phrase on a station wagon’s back bumper, it affected me on two fronts: one as a teenager with anti-conformist leanings and, more importantly, as a drummer. This was before social media when a bumper sticker was a prime method for sharing opinions with strangers.

I knew the message was niche, but I was glad to see someone expressing a preference for a human drummer like me over a machine that could produce beats with mechanical precision.

With time, I learned not to feel so apprehensive about drum machines. Sure, they have no soul, but neither do real drums, nor guitars, nor oboes. All musical instruments are soulless; they’re just tools. Behind every musical tool though, there’s a human being making an artistic choice.

So ultimately, the big takeaway message I got from the bumper sticker isn’t so much that drum machines don’t have souls, but that artists do.

A lot has been written recently about how AI-generated art, the robotic production of fully imagined artwork based on verbal prompts from a human, will soon displace working graphic designers, painters, and visual artists. That’s a worthy concern, but don’t art consumers ultimately get the final word? Not everyone thinks of themself as an artist, but just about everyone has opinions about art, music, film, literature, and other art forms. Thus, everyone will have a say in AI-generated art’s future.

Innovative technologies, like drum machines and oboes, have altered the course of art creation throughout time by adding to an artist’s toolbox, and crabby people like me have complained about these new technologies almost every step of the way. But with AI art generators on the precipice of replacing human artists, consumers of art have a moral decision to consider.

“A love of art seems, automatically, to be offered as a sublime human experience,” says the late art critic John Berger in his influential 1972 BBC documentary series “Ways of Seeing.” One of Berger’s premises is that art shouldn’t just be enjoyed, but also scrutinized for context. I rewatched the series hoping to glean what Berger might have made of our new AI technology. Here, Berger was spelling out the sentiment of other art critics clinging to the “old approach” of enjoying art as a stand-alone piece rather than including historical context and other factors which could color how a piece of art is perceived. “If the experience of art is sublime,” Berger says, “it looks as if it can be sublimely independent of a lot of other values. So perhaps we should be somewhat wary of a love of art.”

I would have a difficult time defining exactly what I look for in art. What I do know is that my taste in art is unique to me. I like some things, dislike others, and have nuanced feelings about everything else. But when I like a piece of art, I tend to want to know the context that led the artist to express what they did. After finishing a novel I like (or dislike), I usually check out the author’s Wikipedia page to see if I can learn more about why they might have written it.

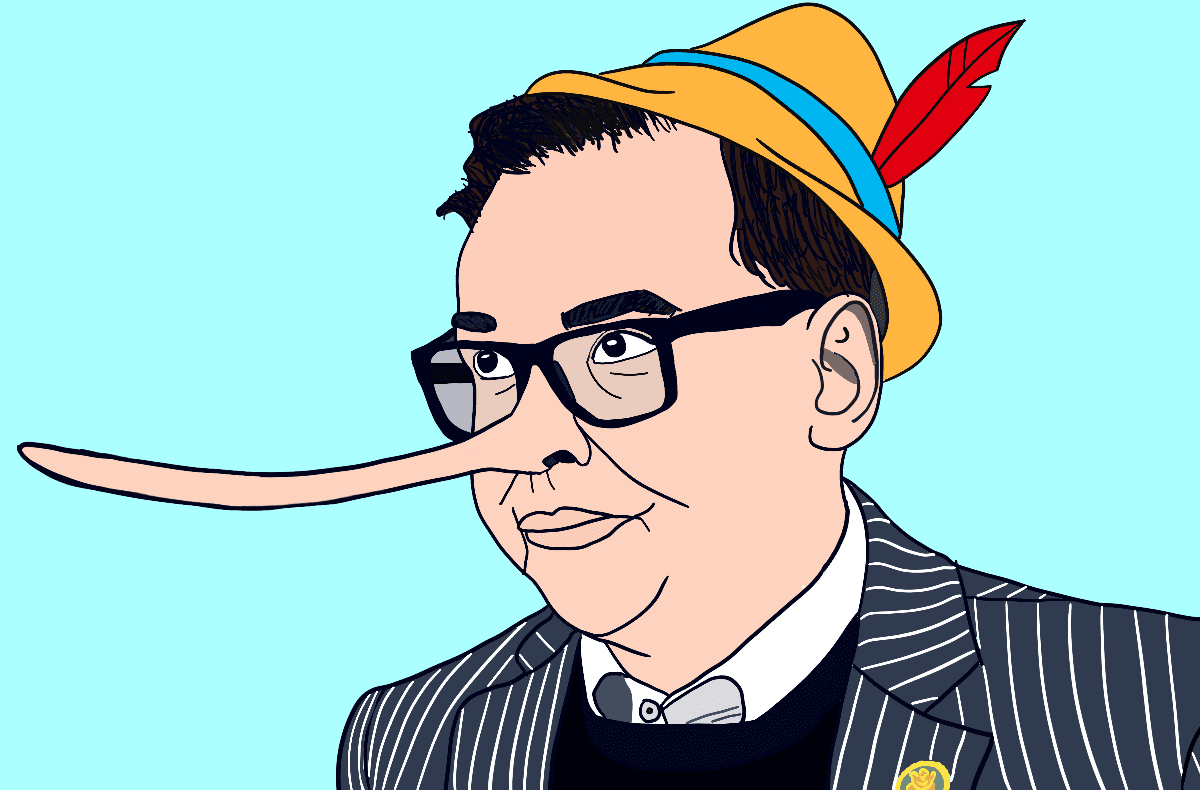

Lately, I’m having the experience of seeing images posted on social media that I like or find interesting, only to learn they were created using an AI-art generator. Very quickly, that same image becomes a grand disappointment. It stops being ART and instead becomes ART*. However much I enjoyed it at first, the image will never lose that AI stink. I’m unfortunately finding myself eyeing all images skeptically now, wondering whether they were made by a who, or by a what.

With AI art production, who’s the artist? If I commission a human painter to paint a specifically-detailed portrait of a woman playing an oboe in a tropical-themed bowling alley, am I credited as the artist because the prompts were mine? I think most people would say no; the artist is the person wielding the paint brushes.

But if I commission an AI art generator to create the same image, by some miracle, I’m the one credited as the artist. How is that fair?

AI generators are the fabricators, the skilled labor, and the tools themselves. But an AI art generator, being merely a tool, has its creative limits. Yes, it can create a wildly detailed image based on a human’s prompts, but it can’t experience a life that informs its craft, skill, or means of expression. It has no taste of its own, nor does it collaborate, nor does it contribute creative intent. It is a robot that follows orders and has nothing it wishes to express on its own.

In other words, you might say AI generators have no soul.

Traditionally, artists have used tools to create their art. But now, with AI generators, the tools are creating the art all by themselves.

Is this what we mean when we talk about separating the art from the artist?

There’s no denying the breadth of AI’s capability to create artistic images, but we, as human consumers of art, must confront the costs of embracing a new technology that cuts artists out of the equation. Will we accept this as the new way to experience art?Some people are taking for granted that our futures are completely in the hands of the companies behind the rise of AI technology, but ultimately it’s the people, the consumers, who decide what’s hot and what’s not. Consumers have spoken up before in other areas: we demand our food be organic, our meat humanely-raised, our clothes not produced with sweatshop labor, and our products made from recycled materials. We demand these things because we’re up against people who don’t seem to care either way.

Now the time has come to demand how we enjoy our art. If we want our love of art to be that pure “sublime human experience” John Berger warned us about, we need to know we can enjoy our art with a clear conscience. Or, to quote Berger once again, “Everything that is shown through these means of reproduction…must be judged against your own experience.”