Much of human action is the consequence of influence. Whether the source is ethical or not, conspicuous or clandestine, influencers use words and examples to achieve objectives by creating temptation so compelling that fantasies seem in grasp, often driven by the potential for material gain.

Their application is informed by an assessment of the target: sometimes, this is purely instinctive; at others, meticulously researched. This is not just true of small-scale social interactions: the same principles apply en masse. In global investment scams, we are exploited by false words and filled with vain promises of amassing a fortune and quickly. But beware of “Greeks bearing gifts.”

Schemers cut from the same cloth as Charles Ponzi understand our susceptibility. They are framed to be likable as well as appearing expert. They have the skills to trigger excitement while capitalizing on herd mentality and our innate fear of missing out.

Time only has refined Ponzi’s 1920s playbook. Whatever the criminal mechanics may be, with each Christmas that passes, so does the exposure of yet another elaborate scheme designed to purloin billions from an equal number of gullible innocents.

This year, just as we were coming to grips with the aftermath of Theranos, news broke of an even bigger heist; that of Sam Bankman-Fried and his FTX offshore cryptocurrency empire. It was all a con. Or at least, that’s the allegation.

And so yesterday’s pillar of high-wealth altruism, who, despite his 30 years and slovenly gamer-kid appearance and who somehow had amassed the fortunes of Solomon through his mastery of the markets, is today indicted for fraud. How could this be? A tee-total, vegan-eating, mop-haired nerd who—when not exercising his trading genius from a futon in his $40m Bahamian love pad—fought climate change, promoted animal welfare, and rescued needy children from poverty. Surely not! Unless, of course, that was all a ruse. After all, what appears outwardly as a sheep could well be a ravenous wolf.

But so compelling was the MIT graduate’s appeal that big finance names, such as Sequoia Capital, Softbank, and Blackrock, together invested hundreds of millions. The corporate media idolized him. And he was endorsed by major public officials. Bankman-Fried reciprocated, donating vast sums mostly to Democratic Party interests—perhaps to sway policy in his favor. As the blame game plays out, duped investors pursue the household-name celebrities recruited to endorse him and his scheme. What should we say about these supporters? Were they willing accomplices, useful idiots, or merely badly advised? Whatever we decide, it will do nothing to help those of far more modest means who now face Christmas having lost their life savings.

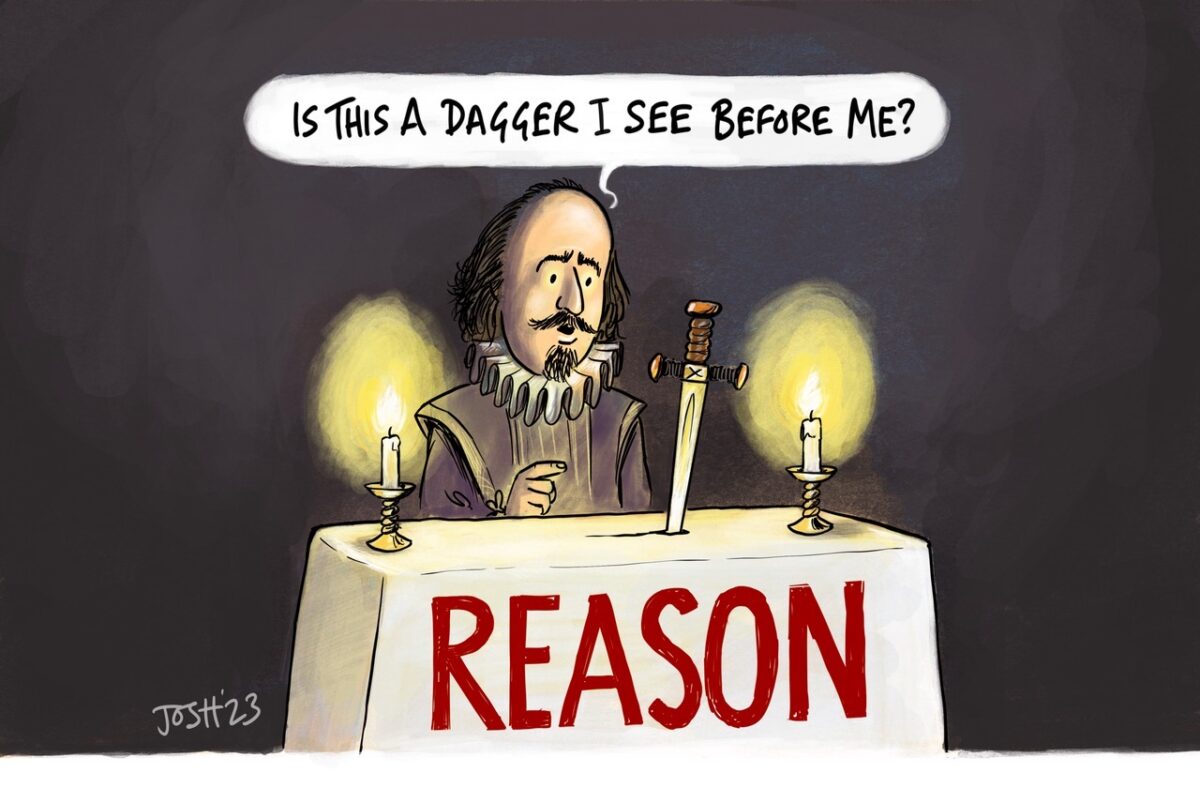

The New Year will bring further FTX revelations: more defendants, more corruption, and more clues that would have given the game away if only cool reason could hold steadfast in the face of avarice and temptation. But will its fallout make us more impervious to future graft? Sadly not.

Whenever the subject is particularly complex, the prospects for successful scamming increase. We Brits have a saying: “bullshit baffles brains.” By using unfathomable technical terminology, presenting the odd graph, and claiming to be able to predict future outcomes with Delphic oracle confidence, they hoodwink us. Rather than engage in skeptical inquiry, we are more likely to take the line of least resistance: to believe. Swindlers know it is far easier for us to feel we can trust an expert rather than getting our heads around something complicated and about which we are not really interested. And few grounds are more fertile for cultivating bamboozlement than in the world of cryptocurrency.

So, beware the false prophets of crypto. Because, as we should know by now, the complacency of fools destroys them.

But one good thing will come of the FTX saga for sure: another truly gripping Netflix miniseries.