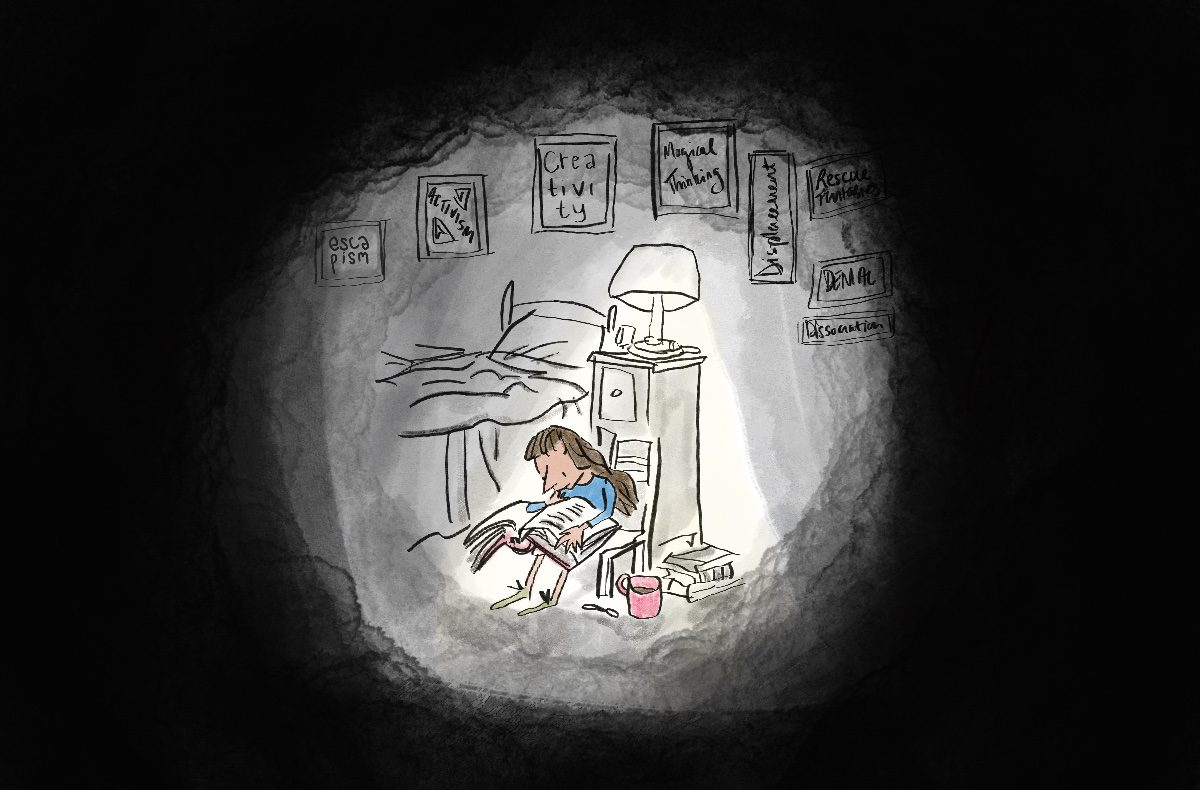

Illustration by Nikki Muller

Roald Dahl’s classic children’s book Matilda is a fictional story about Matilda Wormwood, a young, misunderstood, genius child who has grown up with abusive and neglectful parents resenting her existence. She attends a school run by a horrible headteacher named Miss Trunchbull, who tortures pupils by locking them up in a cupboard lined with nails, spinning them around by their pigtails, and force-feeding them. Not very much is going well for Matilda other than the few supportive people she has in her life: Lavender, her friend from school, Mrs. Phelps, the librarian who fosters Matilda’s love of books and storytelling, and Miss Honey, Matilda’s class teacher who recognizes her potential and adopts her at the end of the story. To make matters more fantastical, Matilda discovers in addition to her love of literature that she has superpowers, and uses them to get back at her abusive family and Miss Trunchbull. The story ends happily, with Matilda having succeeded in breaking free from the chains of her personal oppression in a narrative of hope, personal agency, and good prevailing over evil. Since Dahl first brought the story to adoring fans in 1988, his book has since been turned into a movie and a musical stage production. Most recently, that musical was adapted into a film of its own, Matilda the Musical, which, having loved the book as a child, I watched as soon as it came out.

I’m not sure why I viewed the new musical movie with fresh eyes. It might be because I’ve grown in age and life-experience since my childhood days of reading the book, when I was relatively unaware of its sinister undertones, or it could be that this movie was simply darker and more explicit than its former adaptations. What I am sure about is that Matilda suddenly took on a new meaning for me. I was aware of a new narrative pervading the film, one that seemed so jarringly obvious it pushed all other narratives into the background as I watched.

“Once upon a time there was a little girl who was trapped. This is the story of her great escape.” Matilda is about trauma and trauma responses—primarily Matilda’s trauma, but not exclusively. It is about the length to which our minds and bodies adapt to help us survive unbearable circumstances, the extent to which being ‘trapped’ during childhood leaves enduring scars that call for profound coping mechanisms.

So what does Matilda do in order to cope? What can we learn about trauma responses—and responses to difficult life circumstances more generally—by analyzing her behaviors?

First, we can see that Matilda is a classic example of someone whose real world is too painful to be present in, and so she avoids it by mentally escaping to a safer fantasy world. Teaching herself how to read from a young age and spending hours in her own company (think hyper-independence and excessive self-reliance here); she loses herself in books written by others, or in the elaborate stories her rich inner life allows her to create. Such storytelling proves to be both a form of escapism and a way for Matilda to process her trauma: by displacing her own feelings onto the characters in her story and sharing that story with Mrs. Phelps, she can indirectly express and receive validation for her experiences.

Trauma can have an effect on creativity, and creativity can have an effect on trauma. Matilda seems to experience an overwhelming, often intrusive imagination: “It just comes to me in…fizzes.” Her creativity spins a narrative that has her own bad experiences and rescue fantasies leaking through it. When Matilda tells her story, Mrs. Phelps expects the ending to be happy. Instead, Matilda introduces dark turns of events time and time again, with constant highs and lows. This, and the unpredictability of when the “fizz” will return and what it will be like is all indicative of Matilda’s chaotic real-life narrative, with uncertainty and disappointment its main characteristics, as well as her deepest wishes for loving parenting, acceptance, belonging, and relief from suffering.

Matilda’s use of creativity is in opposition to her denial: the way in which she assures Mrs. Phelps that her parents can’t wait to see her after a long day spent in the library. We can see from this that seemingly contradictory coping mechanisms can sometimes coexist: whereas denial, avoidance, and escapism may serve to provide distance and withdrawal from the trauma memories, creativity and indirect self-expression—while still holding the potential to contain elements of avoidance in them—serve to bring the trauma memories closer, albeit in a way that makes them more digestible and easier to process.

Another form of mental escape is dissociation. When everything in Matilda’s world just feels like too much, she experiences a relentless “burning” inside her that leads to intense physical symptoms, “and suddenly, everything, everything is…quiet.” Such a “silence” that’s “not really silent,” perfectly depicted in the movie as someone floating in the clouds, refers to the feeling of numbness, of being disconnected from one’s thoughts, feelings, and surroundings. Matilda even sings: “and though the people around me, their mouths are still moving, the words they are forming cannot reach me anymore.” She is relating to her world as though she is on the outside looking in, unconsciously utilizing a survival mechanism that helps her stay physically “with it” but mentally far away. While such a coping mechanism certainly has its place when dealing with here-and-now assaults on the psyche, we can also see how it makes Matilda feel “out of it”—she wonders whether “inside my head, I’m not just a bit different from some of my friends,” and she questions whether others are able to fully understand even the simple things going through her mind, such as the color “red.”

Closely linked to Matilda’s use of fantasy as a coping mechanism is her magical thinking. Magical thinking is when one believes they can influence the outcome of events in the world by doing, thinking, or feeling something that has no causal connection to that event. Matilda has the ability to perform telekinesis, a hypothetical psychic ability that allows her to move objects using her eyes without physically interacting with them. Although Matilda actually has the ability to use her mystical powers, many trauma survivors demonstrate an overwhelming conviction to magical thinking as a way of coping with helplessness and powerlessness, and a means to feel in control when faced with chronically uncontrollable events. Matilda uses her magical thinking to channel her internal rage into fighting injustice—“the noise becomes anger and the anger is light”—which many trauma survivors also do in the form of activism. Those who have experienced personal injustice can often be very passionate about fighting injustice in the world at large: “we’ll be revolting children, ‘til our revolting’s done.”

So: we’ve seen examples of escapism, hyper-independence, displacement, creativity, rescue fantasies, denial, dissociation, magical thinking, and activism in Matilda the Musical. These coping mechanisms are explanations, not excuses for future maladaptive behaviors. It’s also important to note that none of these coping mechanisms are “right” or “wrong.” Nor are they all specifically rooted in trauma: you may consider yourself a creative activist with a tendency to daydream for most of the day, and that might have nothing to do with anything traumatic for you. Sure, some of these coping mechanisms are probably healthier and more integrated than others. But when we’re in survival mode, these are primarily utilized in an unconscious way. Which is to say our minds employ them to help us get through really challenging times, and they protect us.

It is vital to remember this if you recognize any of these coping mechanisms in yourself, especially the ones that might become maladaptive if they stick around for too long: they protected you. And when the difficult time passes and you find yourself in a safer place, then you can unpack your coping mechanisms and decide if they’re still serving you or not, with compassion and awareness of their initially helpful purpose.

In the film, Matilda perseveres and gets to a safe space with the support of her coping mechanisms, but what we don’t see is the story of the years after. Once she is safely living with Miss Honey, she might maintain her passion for literature and her creativity, but perhaps she’d be less pressed to dissociate or rely on her “powers” for safety. And so, while the film has a happy ending, it’s important to realize that moving towards safety and inner peace in real life will require a lot of work—and certainly more than can fit into one sitting in a movie theater.

That being said, there are many different ways to do this kind of inner work, and it is certainly possible for everyone to find their own, unique path to healing. And as Matilda teaches us, the power of hope is an absolutely invaluable companion on this journey.