Those who have crossed

With direct eyes, to death’s other Kingdom

Remember us – if at all – not as lost

Violent souls, but only

As the hollow men

The stuffed men.

T.S. Eliot’s The Hollow Men illustrates a harsh reality that has persisted since the very origins of socially constructed gender norms: that many men, more so than women, feel that they have to suffer in silence. Only around a third of referrals to UK mental health services are for men, and whilst it may seem plausible that this is because men experience fewer mental health problems than women, this is evidently not the case, given that three times more men than women die by suicide. It begs the question: what on Earth is going on? And more importantly, what can we do to stop men from becoming “hollow” and “stuffed” in ways that are clearly detrimental to their mental health?

A few weeks ago, I attended an online conference run by The Weekend University on Men’s Mental Health. It was too inspirational to keep to myself, so I took to social media straight away to tell the world what an amazing event it was. And yet, I felt compelled to do more with what I learned. Especially now, during Men’s Mental Health Awareness Month, I feel that it is particularly important to be having open discussions about all things masculine and how they relate to mental health.

So, this month, I’m crediting the ideas in this article to the expert men I heard speak at the conference: Dr. Nathan Beel, Senior Lecturer and Counselling Discipline Lead at the University of Southern Queensland, Terrence Real, internationally-recognized family therapist, speaker, author, and founder of the Relational Life Institute, and Eldra Jackson III, writer, public speaker, and co-executive director of Inside Circle: a transformational healing organization that leads group therapy for justice-involved youth and adults. I highly recommend reading about some of the incredible work these men have done. If you’re looking for a good place to begin beyond the hyperlinks, do yourself a favor and watch the short but powerful documentary, Beyond Men and Masculinity.

“We are fish and the patriarchy is the water we swim in.” This powerful statement by Terrence Real is an important starting point when analyzing why men are less likely to discuss or seek support for their mental health issues. We often hear of the patriarchy as the male-dominated form of society in which we live that subjugates and oppresses both women and those who do not conform to hegemonic gender roles. Yet as much as this system is harmful to women and nonbinary people’s health and well-being, it is also deeply damaging to the men it allegedly benefits.

The patriarchy orders men to follow a code of masculinity that they get shamed for violating. Such a code emphasizes self-reliance, a lack of emotional expression, control, and strength, among other things. It’s important to recognize that this concept of masculinity is a far less rigid expectation in today’s Western day and age than it may have been in the past, but in essence, the patriarchy is still alive and well, which means gendered expectations are too. Little boys are still taught (or rather, wounded), from a scarily young age, that they must disconnect from themselves and others in order to achieve manhood. This manifests in direct and indirect forms of enforcement—from little boys being called “sissies” for crying on the playground to parents speaking to their sons differently than their daughters, using more emotional words with girls, to the gendered branding of boys’ toys as more tough and rugged than girls’. My psychotherapy teacher even taught us of studies that show differences in how mothers hold their baby sons and daughters: holding their boys away from themselves and towards the world, whilst holding their baby girls towards themselves. Even as infants, men are being programmed into emotional distance.

Think about that for a second. Patriarchy is an assault on women that is engendered through the wounding of men. Patriarchy is the poison that supposedly privileges men, but only to the extent to which they can successfully close off their hearts. In the patriarchy, men are dominant, but only under the condition that they behave in closed-off and emotionally-inaccessible ways. Patriarchy is about rationing and policing emotions: “no emotion” or “anger” for men, “helplessness” but absolutely no “unfeminine emotions” for women. What all of this means is that much of the codes inherent within the patriarchy are in direct conflict with men talking about and seeking help for mental health issues.

Asking men to reconstruct this code is in itself a huge task, one that can be more or less difficult depending on various cultural factors, and we mustn’t undermine this. For example, pushing against patriarchal, hegemonic masculinity comes with the risk of men being ostracized from their own communities, depending on where and how they were raised. It is important to reflect on how a traditional emphasis on the man being “the head of the house” or how a cultural focus on “macho” masculinity may be impeding the process of men getting help, especially when such values are associated with shaming therapy.

So, where does the healing lie? First, all of us—regardless of gender—would benefit from checking our biases and attitudes toward masculinity. How are we inadvertently reinforcing the notion that the men in our lives must “stay strong” at all costs? How can we reframe our understanding of masculinity in a way that helps us move from “toxic masculinity” to “positive masculinity”? Positive masculinity is about celebrating, championing, supporting, and valuing men and manhood. It’s about removing the stereotypical “shoulds” of how we expect men to behave. It’s about leading men into healthy self-esteem: yes, holding them responsible, but no, not in a way that is harsh and unloving.

What this can look like in practice for people wanting to help the men in their lives with their mental health is creating a space that is super safe. This means modeling emotional availability and emotional literacy and inviting men to be open about vulnerabilities, but also meeting the men in your life where they are and not incessantly probing them to speak an emotional language they might not be ready for yet. It’s also about simultaneously being mindful of the enormous pressure many men are under to conform to the standards of masculinity, whilst acknowledging male diversity and the way in which such generalizations can sometimes be unhelpful and reductionist.

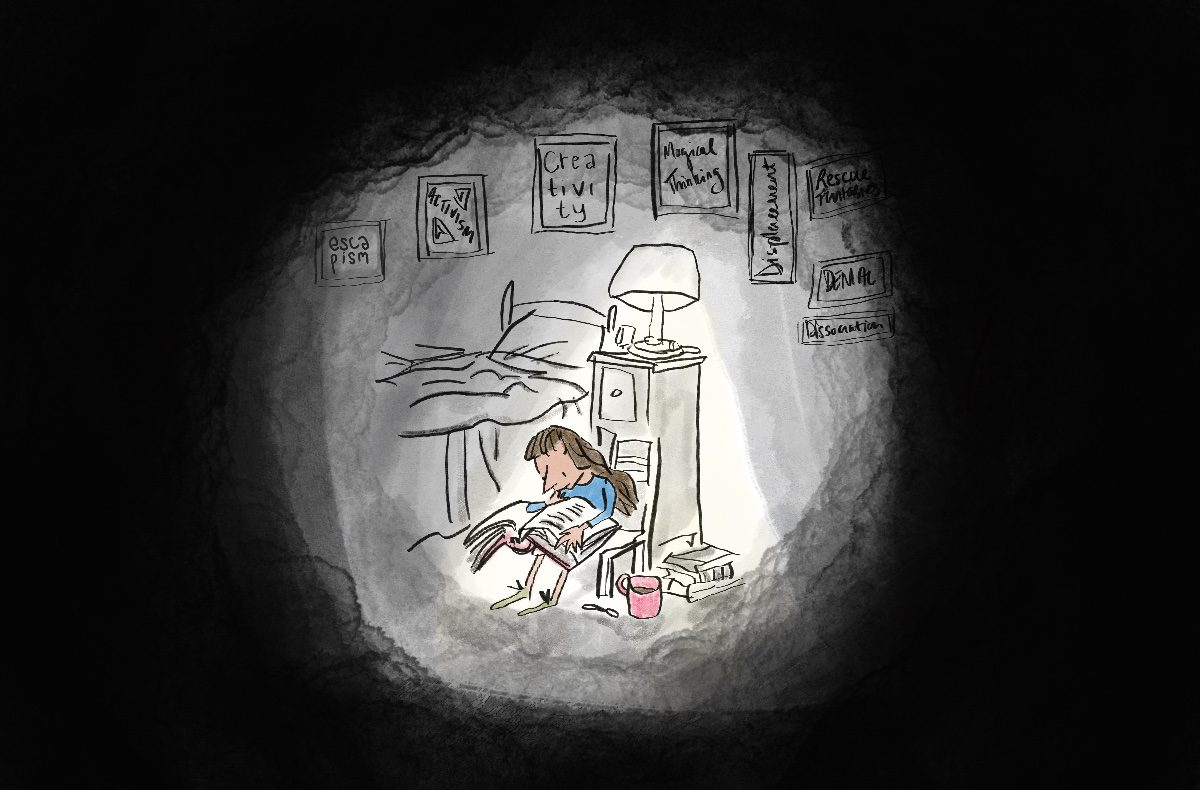

“Hollow men” and “stuffed men” can heal by reconnecting with themselves, with others, with their own feelings, and with the feelings of others. They can heal by nurturing their inner children inflicted with patriarchal wounds. And we can all support ourselves and each other by reducing the stigma associated with men’s mental health and utilizing resources that encourage positive mental health for men.

As ironic as it is that the patriarchy harms the men it allegedly benefits, it’s also ironic that feminist approaches to society can heal them. Contrary to popular misinformation, feminism is not about tearing down men to lift up women. At its core, feminism is about dismantling the patriarchy—which, as we’ve discussed, harms men, too. If we can move past the patriarchy and into a society where all genders and identities are taught compassion and emotional literacy equally, we all will lead happier, healthier, lives. Hopefully, if we all do our part, we can progress toward this future together.