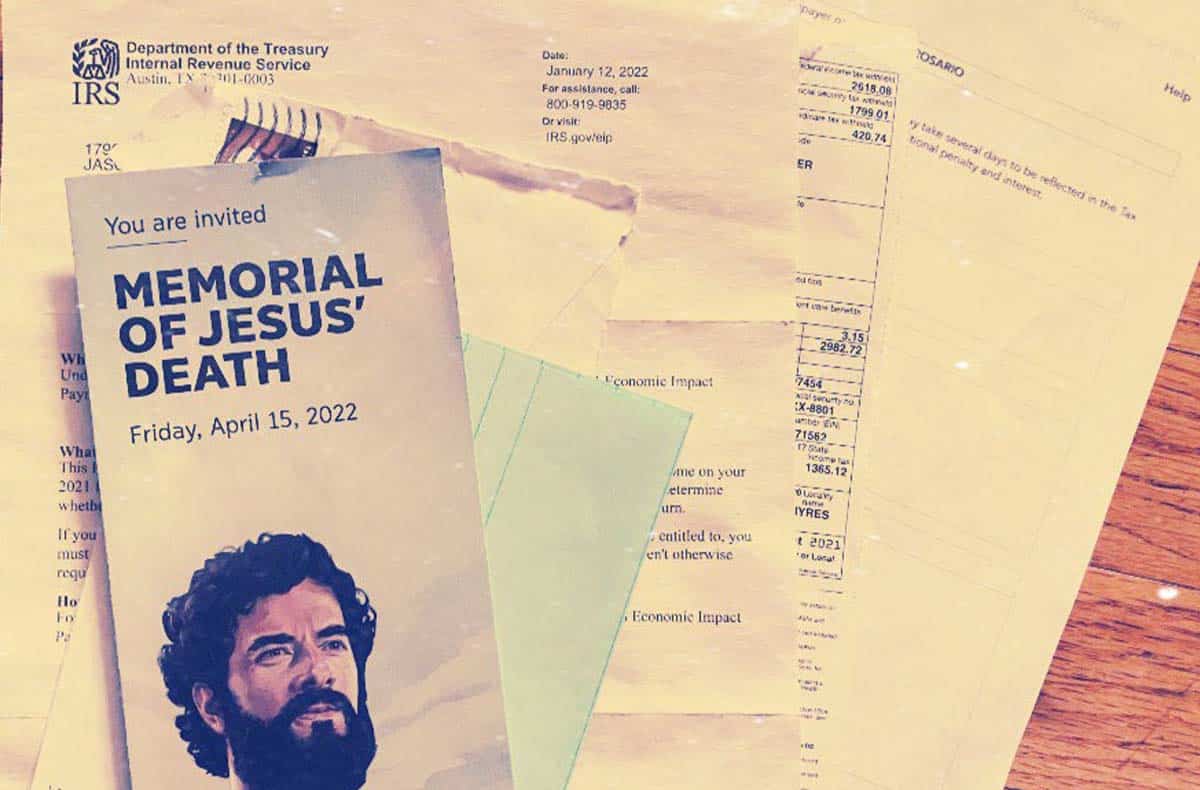

I recently received a mysterious handwritten envelope in the mail. Upon opening it, I found a pamphlet declaring the celebration of Jesus’ death on April 15: I was invited to celebrate across the street at the church I’d volunteered to help with community Covid testing. (According to this pamphlet, Jesus looked an awful lot like Tom Hanks.) I was struck that Jesus’ death also fell on what normally is Tax Day (though this year it’s the 18th.) Jesus died for our sins… and to escape the IRS?

April is a month for the inescapable death and taxes: inescapable in life, but largely absent from an American public school education. Christians spend April reflecting on death, resurrection, and what happens after we die with Good Friday and Easter; the rest of us feel like death as we try to figure out itemized deductions, manically sorting through last year’s bank statements in panic.

Unless you’re awfully good at being a mature and well-sorted adult, you’re likely avoidant about the two, especially if you’re American. As covered in Vox, “[a] 2017 study in the journal Health Affairs found only one in three US adults have an advance directive, including a living will with end-of-life medical instructions, power of attorney naming a person responsible for last affairs, or both” while the National Funeral Directors Association reports that ”[o]nly 21 percent of Americans have even spoken to their loved ones about their wishes.” And according to CNBC, “[a]s many as 33% of Americans procrastinate doing their taxes and wait until the last minute.”

Although I should know better, I absolutely fall into both of these camps. Every year, I start a Google sheet where I tell myself, “we’re going to keep track of our expenses as we go to make next year easier,” and inevitably around June, I completely fall off. Similarly, my then-boyfriend, now-fiance, soon-husband and I have been talking about setting up power of attorney and healthcare proxies for over five years now, having witnessed two family tragedies firsthand in the interim, where not having this legal side of things established was deeply disruptive. We’ve spoken about it with my parents, one who’s a lawyer, the other who worked in trusts and estates, and we all wholeheartedly agreed: this is an important thing we all should do. (They hadn’t either.) Surprise: all four of us still haven’t set this up.

I should be better with death and taxes: it’s in the family. My future husband once made a living selling life insurance, where all day he’d encounter death-avoidant people who’d tell him, “I don’t want to talk about it, that will invite it in.” And until the pandemic forced her retirement, my mother was a fiduciary accountant—all she did was deal with rich people’s wills and paying taxes on their estates. As for me, I had the dubious honor of being one of my first friends to lose a parent: at 19, I became the executrix of my father’s estate. Although being an executrix sounds undeniably cool… it’s not. There were lots of papers to sign. Luckily, mom handled the bulk of the rest while I tried to still be a college student.

Death and taxes both include a whole lot of papers. The difference is, for one of them, the papers aren’t your problem: they fall into the hands of your grief-stricken survivors. No one likes doing their taxes, but we have to. Unfortunately, there’s no taxman coming after us if we don’t set up a will, or make a death plan. It’s just our loved ones, sorting through our mail, trying to find our logins, trying to guess what it is we wanted while dealing with the fact they never get to speak to us again, or hug us, or hear our voice. So really, not having a death plan-—like the majority of us Americans—is a dick move.

With my dad, I remember searching on Windows for “last will and testament” to find a Word document that started, “there is no last Will and Testament.” It was an informal document he used to tell us to check about his life insurance through work, offer some thoughts on a couple things my sister and I could divvy up, and to make a final dig at my mother for “everything she stole in the divorce.” Classy. We were honestly lucky to even find that—a quick measure created in the moment he’d had an inkling of his mortality before his sudden heart attack.

Covid brought a lot more death into our lives. Two years ago, a mile up the street from where I live on Broadway, the NewYork Presbyterian Hospital had refrigerated trucks set up, as their morgues were completely full of those who’d passed from coronavirus. New York saw its deadliest day from Covid on April 7, 2020. A few weeks later, on April 20, we learned my brother had a rare, aggressive form of cancer. We lost him nine months later: due to the pandemic, I couldn’t visit to say goodbye in person. For me, April is always going to be about death and taxes. It’s not an association I can easily forget.

While we joke about death and taxes being equally inevitable, one of these is far more certain: there’s no creative accounting for escaping the Grim Reaper. Yet ironically, many of us tend to treat death like it won’t happen if we don’t talk about it. The reversal of those previous statistics make it clear: two thirds of Americans do deal with their taxes promptly, because we have to—yet without having their hand forced, the same percentage completely avoids planning for their deaths.

But it seems a shift is starting to occur. Apparently, the pandemic is pushing “death positivity” forward, and millennials as a whole are far more likely to create death plans and engage with thinking about end of life than previous generations.

I’ve taken part in this trend, too. Around five years ago, I attended a death café with my partner—one of the first instances where we started discussing healthcare proxies. Our friend gathered a group of us together, and, following the guidelines of the Death Café website, served tea and cake before arranging a large group discussion and smaller breakout groups. There, we all discussed death in an unstigmatized, low-pressure way: how we felt about it, what we wanted for our own deaths, and all the things you really just don’t talk about until it’s the worst possible time to discuss—or too late.

It was intense, sometimes awkward, but incredibly illuminating. I couldn’t help thinking “how is this the first time I have ever openly talked about this, in this way?” I’d often spoken about losing my father, but never really dealt with feelings towards my own life and death. Granted, I still have shirked my duties in creating my own “death plan,” but at least I’ve gone one step in the right direction in even thinking about the fact that I won’t be here forever. It might be time to hold a “refresher” Death Café: apparently, these are even more popular in our post-Covid world.

Death is what makes life meaningful: we only have so much time. And one of the kindest final gestures to those you love is to make the burden of your passing as light as possible. So next time we gird our loins to do the adult things we hate doing—our taxes—let’s set aside time in that discomfort to create a death plan. Like your taxes, death is going to happen, whether you think about it or not; and handling it mindfully can make all the difference in the world.