I once went to a leadership training-type workshop where the sixty of us present were tasked with each crossing the room in a way unique from one another. This could be walking sideways, skipping, dancing, or any other locomotive variation—dealer’s choice. I sat down, went up into a wheel pose, and bridge-walked the length of the room—it definitely wasn’t something anyone else had done. Everyone cheered. I felt like a badass.

Afterwards, one of the trainers said, “you do realize you chose the most difficult solution, right?”

I felt very attacked.

I’ve never been one to shy away from a challenge. It’s pretty much my M.O., but I don’t think I ever really thought about why until I reached adulthood. This mental health awareness month, I thought I might take a second to reflect on that innate drive, and consider if it really “serves” me.

My entire life, I’ve felt this impulse to take on ambitious projects. It’s behavior that was modeled for me by my dad. This is a man who escaped communist East Germany through an early Berlin Wall, doggedly cutting through section after section of wire before making a mad scramble up and over the final barbed wire fence while being shot at by border guards. He’s also the man who built a full-size igloo in our front yard and engineered a treehouse in the backyard—both projects that had started as “fun” ideas by me and my sister, and were relentlessly pursued to their completion under his instruction well after they ceased being fun anymore. And he’s the man who figured out how to rig up an old antennae motor to a rotisserie spit, running it off the car battery and stabilizing it with a piece of gutter so we could roast a chicken over a fire during a camping trip. Here’s what this monstrosity looked like in action:

Another “dad-ism” was he’d always insist that, if he could cook something just as tasty at home, it wasn’t a dish worth buying at a restaurant. One random night of takeout resulted in him spending months figuring out steamed dumplings, puzzling out how to make his own wrappers, perfecting the pork-green onion-ginger filling, and getting his own bamboo steamer in Chinatown (there wasn’t any two-day Amazon delivery back then). He asked our downstairs neighbors, a Chinese family, for advice on refining his dumpling recipe: they thought he was insane. Of course, you just buy the wrapper in the store. (Naturally, he didn’t quit experimenting until he’d figured out how to make them himself.)

A lot of my friends would marvel at my dad’s single-minded drive, but to me, it was just what you do—and it was an inherited trait. When I was graduating high school, Dad ended his Polonius-style letter of life advice with Ecclesiastes 9:10—”whatever your hand finds to do, do it with all your might.” I always have followed that.

Sure, I’m not an engineer, so there’s less building—and fewer MacGyver-worthy rotisseries. But anything I find to do, you better believe it’s getting done in an unnecessarily extreme way. My running hobby turned into triathlons, which inevitably turned into me doing six full-length Ironman races. (Because if you’re going to do a triathlon, why not do one that consumes your entire life?) The play I created with my partner, which could have just been, I don’t know… a normal play, wound up requiring years of acrobatic training so we could nail the perfect physical metaphors that would realize my initial artistic vision. (Note: neither of us are acrobats. Well… I guess we sort of are now.) And instead of settling for a normal two-week run of the show at home in Los Angeles, we did a full run of 21 performances at the Edinburgh Fringe—having never set foot in Scotland before, no less. Here we are, doing a 15-minute excerpt after already doing a full performance that morning, and before another four hours of busking. (Note: for a self-producing performer, Edinburgh is hell. But it’s a lot of fun if you’re there to drink!)

Unsurprisingly, as a student, I was always a “grade grubber,” always going for the high GPA and awards. And of course, I’m an absolute maniac in the kitchen. I’m a huge cooking hobbyist, and it gives me great joy to embark on all kinds of culinary adventures. What I lack in my father’s engineering precision, I make up for in creativity and sheer power of will. Holiday meals always go from a modest plan to something that will take days of prep and hours of execution, almost guaranteeing a nervous mental breakdown. Ambitious kitchen experiments and my natural attention deficit issues are not a great combination, but I always find a way through. A few triumphs from recent years include a massive sous-vide turducken roulade and an abomination of a timballo genovese (see below—oh, the humanity):

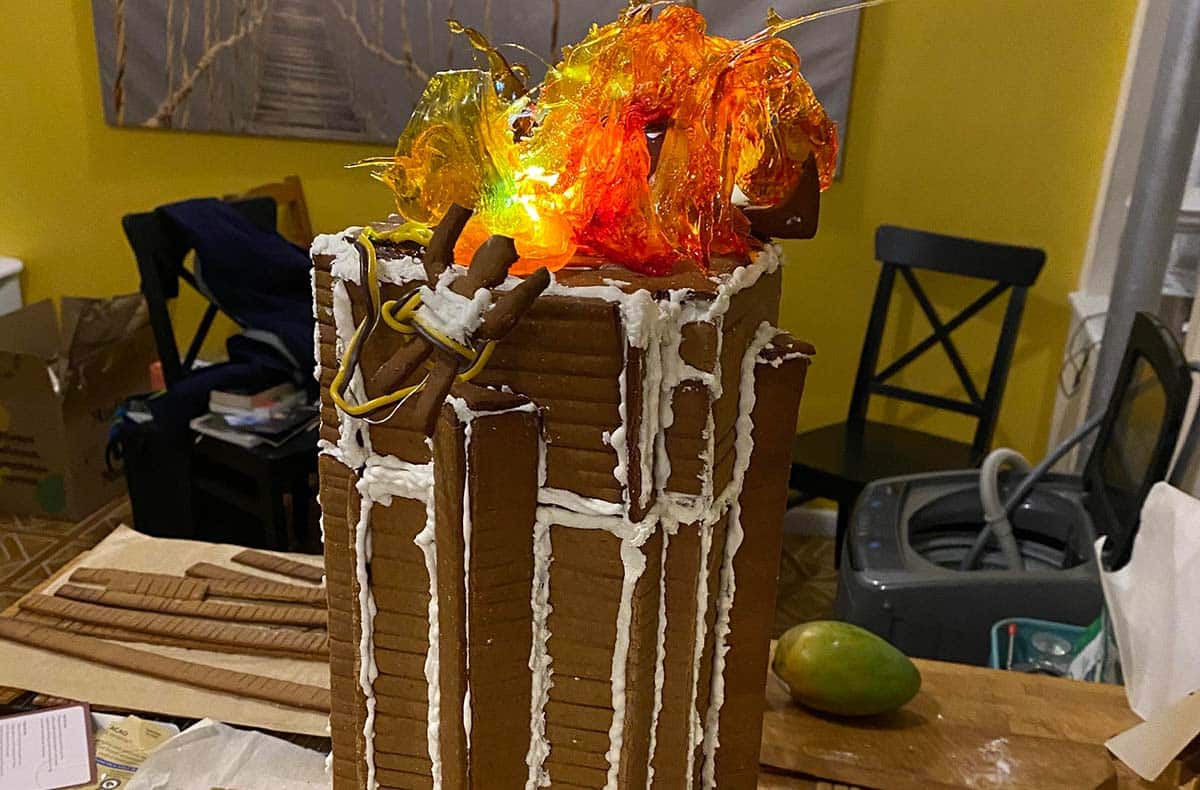

My personal favorite dessert was last year’s Christmastime recreation of Nakatomi Plaza, with a little John McClane leaping from the sugar-flame engulfed rooftop (to explain this piece’s first picture.)

Each and every one of my challenges—creative, academic or culinary—had some moment of sheer panic where I thought “that’s it, I’ve gone too far.” But somehow, I’d keep going, and I’ve always reached my goal in some way, shape or form; the struggle makes the end result seem all the sweeter.

Any time it seemed like I’d bitten off more than I could chew, I did eventually find a way to force it down: it just almost choked me to death a few times.

But in recent years, I’ve started to learn: we can take smaller bites.

Let’s talk about that timballo: the recipe calls for tagliolini pasta, which is an irritatingly obscure choice. I’d ordered some specially online, only to find I needed twice as much (ADD problems.) So I went to three stores, finding nothing, and ultimately decided I would make it myself since the thin flat shape of the pasta press was the only close equivalent I could find.

Of course, I could have just substituted spaghetti. Or capellini. It’s literally smothered in onion sauce, then layered with mini meatballs and a thousand pounds of smoked mozzarella and even more parmesan, crammed in a springform pan and baked. But I WOULD KNOW.

So I spent an extra hour and some change making the damn pasta, just like my Dad and the dumpling wrappers. After, when we all dug into the monstrosity, I learned an important lesson. I really didn’t need to go that extra mile. Making the sauce and the meatballs and all that was enough. At that point, it wasn’t even a meaningful gesture to the family member I’d made it for… it was just feeding my ego.

Today, I’d like to think I’ve learned that, even if I can, I don’t have to do the most. It’s true, I still love to host a good dinner party. But now, I’ll just make one kind of bread, and maybe opt for a simpler dessert or—gasp—even a store-bought one (sorry, Dad!) Because one thing you can’t get back is your time. And spending hours away from friends and family training for a race, or the entire holiday slaving away in the kitchen, is not necessarily worth it.

There’s a second part to Ecclesiastes 9:10. The full verse reads: “Whatever your hand finds to do, do it with all your might, for in the realm of the dead, where you are going, there is neither working nor planning nor knowledge nor wisdom.” Essentially, you won’t be here forever, so spend that time well, and spend it wisely.

There’s nothing wrong with being ambitious. And shooting for the stars reaps marvelous rewards. But you also need to consider what it is you do with all your might, with whom, and why. Whenever my Dad roped my sister and I into a new, singularly-focused mission, it created countless memories together. But when he’d spend hours in the office, editing a project to meticulous perfection, that meant missed family dinners, memories that never happened. Similarly, I quit doing Ironman races when I realized I was investing a ton of time into something that didn’t really move my personal life or career goals forward as a creative person. So instead, I put all that energy into a new pursuit: working on a new play that would have a super cool acrobatic component (had to get in that Ironman energy somehow.) Our countless hours of rehearsal created not only the most meaningful work of art I’ve ever shared with the world, but the most meaningful relationship of my life with my partner and future husband.

So: will I keep “doing with all my might”? Of course, it’s a part of who I am, it makes me, me. But these days, it’s not about whatever my hand finds to do: it’s whatever I choose to do.