In part one of this series, I spoke about the conditions and structure of most restaurants and catering establishments and the way they actually work. It’s not as they are advertised—not some sunshine and lollipop home bakery exercise, and not the watered-down version you see on TV.

(Although ironically, if you see some of the shows Gordan Ramsay does, it says “dramatized” on the credits. Make of that what you will.)

The concept for all of those shows are the same anyway: the restaurant’s failing, they’re forced to use frozen food, the kitchen is filthy, and then some family breakdown ensues. Ramsay and his team give the walls a lick of paint and change the menu. Job done.

Anyway… I’ve gone off topic.

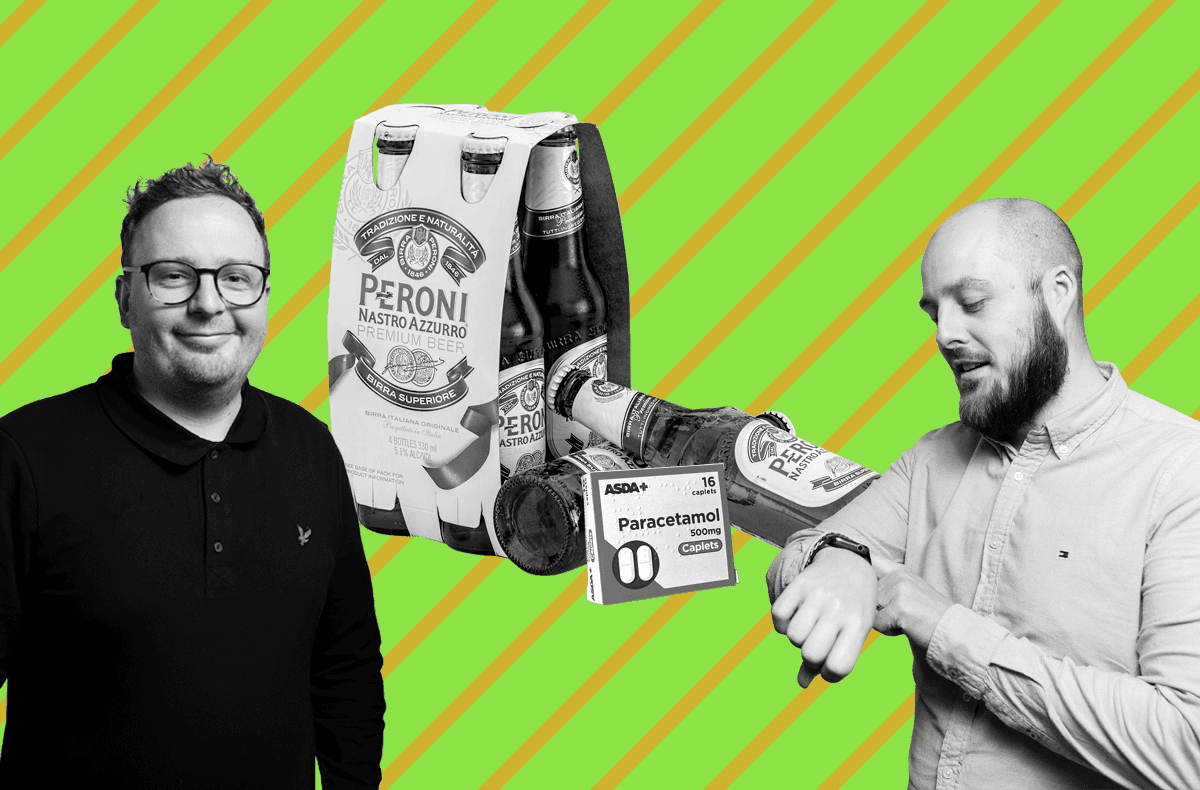

The second part of this series was to discuss the culture within catering, or more aptly named—addiction.

This can come in many forms, and not all are equally harmful—like addiction to work, food, or the will to be better than anyone else. In most cases, you’d think that’s something everyone has, but I’d argue it’s a different breed for those working in hospitality. You’re working 60+ hours a week. These are the nicer, positive, and sought-after addictions.

However, catering is clouded by much darker addictions. Ask anyone you know who has worked in the industry for over six months. They’ll tell you the same as everyone else. Addiction is everywhere.

I worked in the service industry for just over 13 years, and I reckon that, out of the hundreds of people I worked with, I could count on one hand those who didn’t have some kind of addiction.

You’d be hard pushed to find a chef who wasn’t addicted to cocaine, marijuana, alcohol or at the very least, coffee. Randomly I worked with a chef who wasn’t interested in any of that, but was addicted to sex. Additionally, you’d find a minority that were also addicted to pills and any number of other drugs.

This wasn’t always limited to people doing these “extra-curricular activities” outside of work—mainly because you were always at work. So naturally—which feels odd to write—all of these addictions would creep into work. People were either high on drugs, drunk, or down and lethargic on a come down during working hours. It’s a surprise any work actually got done, and that, in an environment surrounded by gas, fire, and extremely sharp knives that no one got killed. Sounds dramatic, but it’s true!

In a few establishments I worked at, we’d get the odd half an hour break in the afternoon during a lull in service just to get out. This would be done on rotation—two would go, have half an hour, two more would go and have their half hour break, and so on.

Can you guess where 90% of those chefs went? Yes. The pub.

I remember once when another chef and I went to a pub, where we both had a soft drink and returned. When asked what we had by our head chef upon returning to the kitchen, he told us to go back to the pub and not come back until we’d had a proper pint. So off we went. Chef’s orders after all.

I must say at this point, of course I had a pint on my break every now and then. I was in my late teens and early twenties, I wasn’t a complete do-gooder. But it was in control, on rare occasions, and not everyday. And I certainly didn’t get completely hammered!

Twice from memory, things went wrong.

Two of the people who went on a half an hour break decided to make it a few hours, came back steaming drunk to the point no one else could take a break because they’d taken so long, demanded I jumped in my car—which I wasn’t insured to drive because I was selling it—and wanted me to go and pick up cocaine for them. Of course, I refused. I was kicked in the shins with steel-toe-capped boots, sworn at, and forced into making an unpleasant decision.

This was at the end of service, when normally you’d clean up your section and then help with the rest of the kitchen. I just did my section and went home. I thought that was the end of it. Turns out my coworker rang the head chef who was off to tell him I’d “walked out.” The cheek of it! We both got suspended for a week, which was mental to me—I hadn’t done anything wrong!

This man clearly needed help. He was deep into his forties, drinking every afternoon and evening—possibly morning, too. Although he had kids and other adult responsibilities, none of this made him grow up.

Ultimately, he got sacked—late on a Sunday night, he was having drugs delivered to that back door as the general manager walked past. Surprisingly the line of “my mate’s letting me borrow his lawn mower” didn’t convince anyone of his innocence.

He’s been to four, five, or possibly more restaurants in the same town at this point, where he’s been fired for similar reasons. He can’t change—and won’t change. Beyond him, I know I could provide you with examples of seven or eight other chefs exactly like that.

When he and I were both suspended, I got a call from the general manager, who asked me what I’d “like to happen.” Despite being incredibly pissed off, I said I didn’t want anything to happen; I had a heart, I didn’t want to see him sacked. I wanted him to have support. “He doesn’t need sacking, he needs help” was my response. That phone call still is vivid in my memory.

And here is where I, eventually, come to the purpose of this article. Addiction is huge in catering, as I’m sure it is in other industries, but because of the way the culture is ingrained, of how common it has become and the fact you can be either disposed of or hired so easily somewhere else once you have a bit of experience, there is no help, no support, and for a lot of people, no way out.

This male-dominated industry prides itself on machismo, a steely, toxic attitude that, when you scratch beneath the surface, reveals insecurities and coping mechanisms to all those hours, the stress, the drugs, the alcohol, et cetera. It’s one big vicious circle of chaos and depression. And no one wants to talk about it.

It is just accepted as part of the culture. You’re the odd one out who doesn’t really fit in if you just want to do your job and go home. That doesn’t seem normal or healthy, does it?

You also have to ask why people are choosing to go down these paths. Sure, it could be solely down to the culture, experimenting, having a bit of harmless fun, but in most cases, using drugs and alcohol in catering offers a release, escapism, a break from the pressures of working in a high intensity environment for long hours with little to no perks.

For many, as in the example I provided, there is no way out. It’s difficult to stop this habitual behavior once you’re in your forties, and it’s even harder to consider retraining and looking for a new career elsewhere. Particularly in this climate, when it is hard enough to find a job.

So where is the support? How can people within the catering industry seek help and support without losing their jobs?

A lot of restaurants are independently owned. They don’t care about people, nor do the big companies. Whoever you are and wherever you work, you are just a number; you can be replaced easily by the next person willing to work all the hours in the world. We’re all just the next chef on the conveyor belt, ready to abuse our bodies in any way possible.

And so the cycle continues, until you intentionally get off—or when your body gives out, or when you simply can’t bear it anymore, as we’ve learned from the tragic passings of even the most successful chefs.

There is no simple solution to this issue: and I don’t have the answers. But what I can do is acknowledge it—and shine a light on this shadow world we’ve left unexamined. The more we speak up and call attention to parts of the world that should change, the better the odds are that progress will happen. Hopefully this will be a small step in the right direction. If this can help just one chef make the better choice, or one restauranteur to take a stand for a less toxic culture in their kitchen, then it was worth the effort.