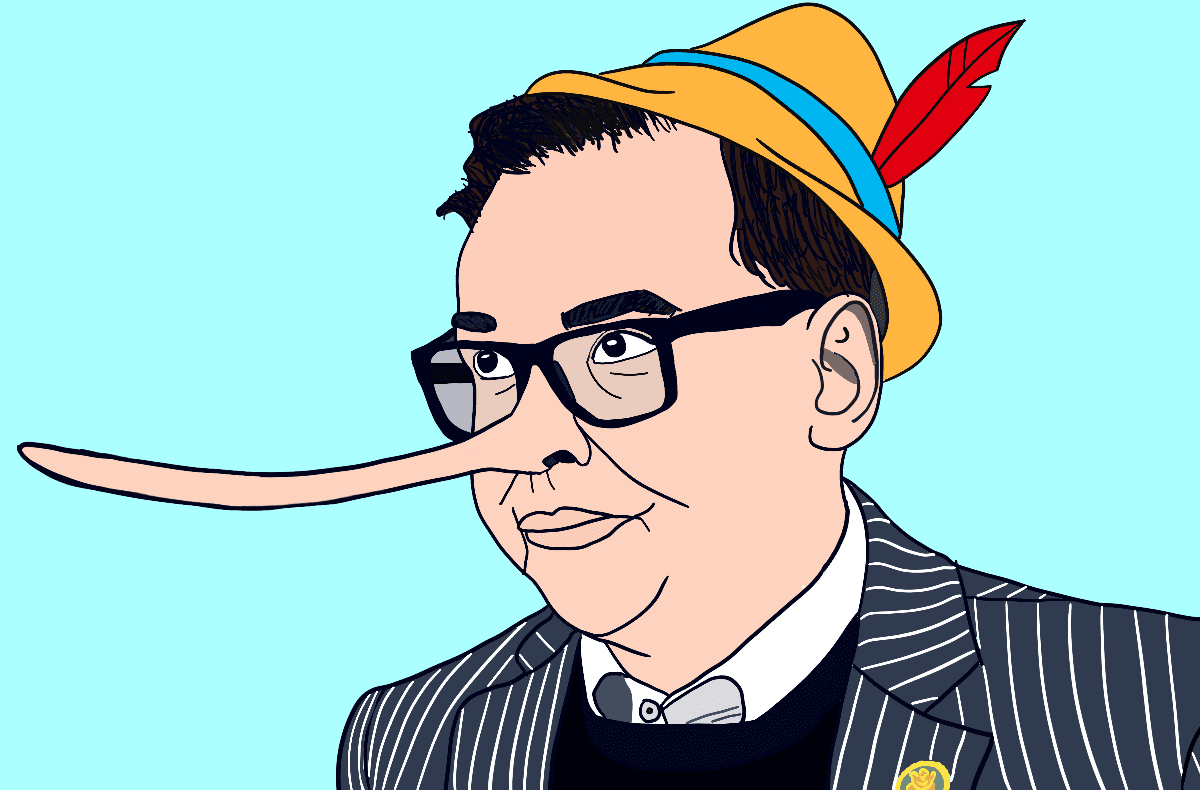

At the time of this article’s publishing, we likely have already passed peak George Santos. Or, at least, I hope we have. I hope the newly-elected U.S. House Representative from New York, who by now is famous for a slate of lies ranging from comically benign—like his claim that he attended Baruch College on a volleyball scholarship (he did not)—to horrifically heartless—such as swindling money raised through a GoFundMe meant to pay for the life-saving surgery of a homeless Navy veteran’s beloved dog (the dog died)—has been sufficiently lampooned, denounced, derided, and that he will soon make his way towards the downward spiral he so rightly deserves.

I feel like I’ve been taking the Santos saga harder than most. The district he represents includes my hometown of Great Neck, a town so affluent I thought I grew up poor. Many of my high school classmates had financial cushions, family connections, Ivy League-level work ethics, and a determination to succeed. Until recently, I thought that a career in politics would’ve been a natural path for some of them, but not for me. Now I know that if I only had the sociopathic will to bullshit about every aspect of my life with reckless abandon, I could’ve succeeded like the best of them.

I’m not built that way. If anything, I’ve been too honest with potential employers. In job interviews, I’ve been prone to downplaying my experience and abilities out of fear of sounding too cocky. The worst I ever fudged my resume was rounding up my college GPA to the nearest tenth decimal. So for me, seeing a maniac like Santos sneak his way into the levers of power is, well, annoying.

It makes me wonder if we, as a society, have lost our ability to be skeptical. Or, have we ever been skeptical enough?

Santos is hardly the only person who slithered their way into our cultural fabric. How often have we engrossed ourselves in recent documentaries with lurid details about charismatic cult leaders? How many visionary venture capitalist CEOs have been revealed as fraudsters? And Anna Delvey; what was her deal?

It’s a healthy thing to be skeptical, and we should be encouraged to question and prod for intent. So what’s keeping us from enforcing robust skepticism? I think it’s good manners.

The O.G. skeptic, the apostle Thomas, A.K.A. “Doubting Thomas,” earned his condescending nickname after not believing all the other apostles when they told him Jesus had been resurrected from death. This shouldn’t be a crazy concept to doubt. In his 1602 painting, “The Incredulity of Saint Thomas,” Caravaggio depicts Thomas harshly as a doting fool poking his finger into Jesus’ wounds, but I applaud the apostle for doing his due diligence—and I hope he washed his hands.

Unfortunately, expressing skepticism usually means crossing a line, poking the bear, or rocking the boat. For example, let’s say there’s a young, charismatic entrepreneur at a party boasting about their new asbestos startup, the polite response is to smile and wish them well in their business endeavors. The skeptic doesn’t do that. The skeptic rightly asks, “Doesn’t asbestos cause cancer?” No matter how genuine your concerns, this isn’t the best way to make friends.

So, when confronted with someone who we think in some way might be scamming us, we have a choice: Do we behave ourselves, or do we speak up?

Speaking up is low on short-term rewards. We risk rankling someone’s mood and alienating ourselves. But some people have the audacity to list themselves as a “philosopher” on their LinkedIn byline, and don’t we want to keep our distance from these kinds of people?

I suspect that if Santos himself was confronted with the asbestos entrepreneur, he’d choose to behave himself. Maybe he’d even gush that the asbestos entrepreneur had a one-in-a-million idea. Maybe Santos would mention that his dad used to be in the asbestos business, and the two of them should partner up. These are the contracts that try our world.

Some veneers are meant to be cracked. It may take a little bravery, but we don’t always have to be fascinated by charismatic imposters. We can be the ones to chip away at their egos and rein them in. We might not always prevent an outbreak of fraud, but at the very least, we’ll be less likely to join a cult.

Could a healthier grasp of skepticism have stopped George Santos before his election? I think so, but I can’t be certain. Then again, having graduated from the Sorbonne with dual PhDs in psychology and having written the foremost volume of books on the study of the pathological mind, as well as being an Olympic pole vaulting finalist, prize-winning llama breeder, and inventor of the fidget spinner, you can trust that I know what I’m talking about.