We live in an era of endings. An era when, briefly, we become aware of a sense of generational shift; when we gain a heightened consciousness of the prelapsarian splendour of figures we had taken for granted. I could be talking about the Queen, but amongst the frenzy of obituaries for her late Majesty, another visionary left us. Jean-Luc Godard, filmmaker and poster-boy for the French New Wave died last week, aged 91, by assisted suicide in his hometown of Rolle, Switzerland. In death, as in life, he did it on his own terms. And what terms they were: to watch a Godard film is to be upended and confused, to be maddened by the abruptness of his narrative form and left stranded in a universe of the abstract. In an age of TikTok and visual experimentation, it is all too easy to forget what he gave us.

Godard stormed onto the scene with Breathless in 1959, the story of a young American girl in Paris played by Jean Seberg who enters into an ill-fated love affair (and pregnancy) with lusty bad boy on the run—Jean-Paul Belmondo. Perhaps Godard’s best-known film, Breathless came on the heels of his sometime friend Francois Truffaut’s The 400 Blows, loudly announcing a sea-change in the direction of cinema. Few artists are able to galvanise a generation of their contemporaries in this way; Picasso did it along with Schoenberg, but Godard’s masterstroke was his insouciance; where he led, others followed. In its strange fusion of philosophy and jazz, alongside the technical short-circuitry of the camera direction and the infamous “jump-cut”, Godard’s opener gave audiences the sense of an individual thinking concurrently with the pace of the film and lifted the curtain on the directorial persona, one which the French New Wave never entirely shrugged off. Just watch the cinema of Claude Chabrol, Jacques Rivette and Eric Rohmer and witness its variations on the artistic and the personal, embodied literarily in the ineffably French form of autofiction by Philippe Lejeune. Quite suddenly, cinema, not literature or painting, presented itself as the art form of a generation and the blueprint of the individual, an idea that came to political fruition in the events of May ‘68.

Moving away from the scripted symmetry of Hollywood, Godard’s films were what we might call a mash-up of the particularly French variety: metaphysical quotes and philosophical allusions thrown in amongst his friends and wives (Anne Wiazemsky, to take one example), cast in leading roles. Moving between various registers was not, however, without its difficulties. As his star rose in the 1960s, his politics and his art became confused, pulled in different directions. Le Petit Soldat, made in 1963, took aim at the French involvement in the Algerian War for independence. The film was subsequently banned from cinemas for three years, turning Godard into an establishment pariah and highlighting the dangers of welding one’s artistic capital to the political, a risk many contemporary directors such as Gilliam, Scorsese and Tarantino now make routinely. Much later, Godard would face charges of antisemitism in response to his championing of the Palestinian cause, leading French philosopher Bernard Henri-Levy to remark that Godard was “a man trying to cure himself of antisemitism”.

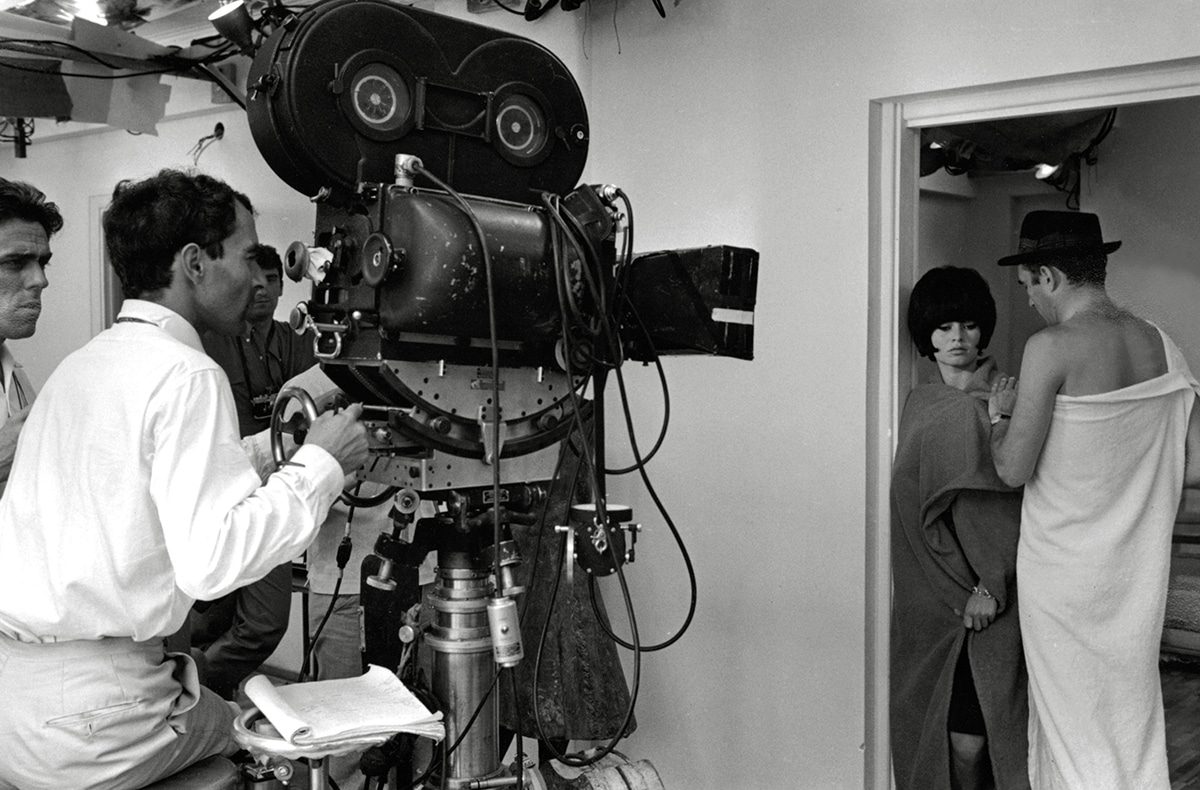

From such complicated ambitions emerged my favourite of Godard’s films, Contempt, starring Brigitte Bardot at the zenith of her international stardom. Contempt, the film adaptation of Alberto Moravia’s novel Il Disprezzo, settles on the struggles of the artistic life in the morality tale of a penniless screenwriter, Paul (Michel Piccoli) hired by money-grabbing Hollywood producer (Jack Palance) to rework the script for German director Fritz Lang’s (played by himself) screen adaptation of the Odyssey in Rome. I first watched Contempt in a fall semester at graduate school as the leaves on campus turned from green to red and summer faded from memory. In my mind, the film and the fall are welded together with a sense of melancholy—accompanied by Georges Delerue’s extraordinary score—which only Godard could create. All this with Godard’s trademark sense of humour, writ large in the sardonic use of Bardot’s derriere and Godard’s wry remarks on the end of an affair in all senses: artistically, romantically and culturally.

Like the Queen, in death Godard risks being eaten by his own myth. His much-quoted aphorism—“You don’t make a movie, a movie makes you” or “At the cinema, we do not think, we are thought”—continue to tie us up in knots, searching for the man behind the mask despite his overwhelming body of work that, notionally, gave us so much of himself while still leaving us none the wiser. In his later work, Godard became even more gnomic and out of reach, making such extravagantly strange films such as Film Socialisme (2010), a collage of images and ideas showing people drifting aimlessly on holiday, much of it filmed on a cruise ship.

For me, in these later films, it is as if the great Godard had already left his audience, fulfilling his prophecy made in 1967 that cinema was dead (without him, one imagines): “End of Story—End of cinema”. As Godard knew all too well with his infamous jump cut technique, the end is subjective, a point in time to be finessed rather than accepted.