Pedestrian deaths have increased dramatically in the United States over the last few decades. But don’t worry: now, more than ever, the car that kills you is likely to be electric!

A decade ago, fully electric cars were a rarity on American roads. Hybrids like the Toyota Prius had proven popular, but zero-emissions vehicles were so uncommon that someone made a movie investigating their disappearance. One theory holds that General Motors self-sabotaged its first electric vehicle, the GM EV1, in order to poison the well of electric cars in the American market.

Between the EV1’s demise in 1999 and the debut of the Tesla Model S in 2012, electric cars were deeply uncool. Hybrids may have sold well, but a huge chunk of the population quickly wrote them off as virtue-signifiers for effete liberals. Whatever else one thinks about Elon Musk—I think he’s a tool—he undeniably changed the perception of electric vehicles. Taking design cues from Jaguar rather than Kia, and incorporating Easter eggs that made the experience of owning a Tesla similar to playing a video game, Tesla brought electric cars into the mainstream.

This success came despite fierce opposition from the oil lobby, car dealers, and other automakers. Now that Tesla has established electric vehicles as the way of the future, however, its competitors have rushed to electrify their own fleets. Yet even as GM and Ford have turned face, going all-in on electric vehicles, something odd has happened: American cars have gotten bigger.

America’s love of squirrel-squishing, deer-smacking driving machines was already a punchline in the late 90s, but our cars have gotten noticeably larger since then. Size, or the lack thereof, is part of what made the Prius a laughingstock to proto-Trumpians. Real American men drive big, American cars, while pretentious globalist urbanites drive little, foreign hybrids. But if American consumers were at a crossroads in the 2010s, forced to choose between gas-guzzlers the size of armored vehicles and eco-pious micro-machines, manufacturers have finally found a third way: making electric cars ludicrously big.

Electric vehicles still make up a small percentage of total sales in the U.S., but that number is projected to rise to 40 percent by 2030. What’s strange is how few of these cars will be sedans. Four out of five new cars purchased in the U.S. last year were trucks or SUVs, up from just 54 percent a decade ago. Even as they go electric, American automakers are leaning into this trend, abandoning classic sedans like the Ford Taurus or the Chevy Impala in favor of SUVs and crossovers.

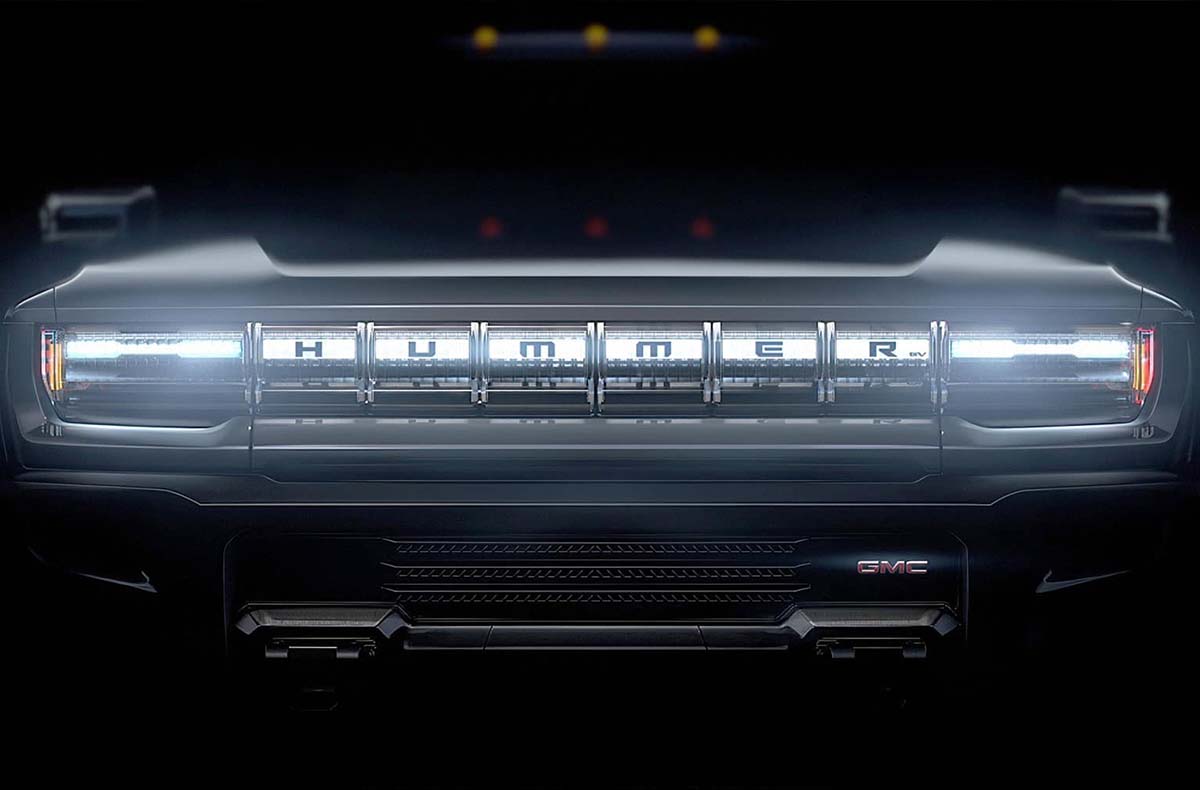

That’s how we get monstrosities like the new Hummer EV, a Lebron James-endorsed all-electric SUV weighing in at a little under five tons. Take a look at the “declassified” videos on the EV’s website, and note the selling points: It can go from zero to 60 in a little over three seconds, remarkable acceleration for a car of its size. At 79 inches, it’s inordinately tall and capable of getting six inches taller to “surmount tough obstacles.” In addition to a high-definition dashboard screen that gives the driver useful information such as speed and mileage, there’s a second screen the size of an iPad, featuring a selection of apps and graphics from the studio that makes Fortnite. You can use this screen to access the camera app, where you can select any of the whopping eighteen on-board cameras that “help you maneuver in almost any scenario.”

Like most SUV and truck commercials, the EV’s marketing materials imply that drivers will use it to explore the most difficult terrain that America’s western Badlands have to offer. This assumption runs counter to market research, which has found that only a third of truck owners go off-road more than once a year. This finding suggests that precious few EV drivers will ever need CrabWalk mode, a gimmick that was no doubt designed to keep pace with the GOAT Mode offered by the new Ford Bronco. Take a look around the SUV market and it becomes clear that the EV is merely the latest entry in an automotive masculinity competition, designed to assure drivers that they can be rugged badasses even if their car only burns fossil fuel indirectly.

It’s hard to imagine Hummer’s suburban clientele needing CrabWalk mode or a camera that shows the terrain directly beneath them. It’s harder to imagine why the average motorist would need to go from zero to 60 in three seconds or conduct their grocery run from seven feet above the ground. What’s not hard to imagine is the danger that cars like the EV pose to everyone around them.

There’s an undeniable correlation between the size of cars and the number of people who die in traffic accidents every year. The number of Americans struck and killed by cars has reached its highest level in 40 years, more than doubling between 2009 and 2018.

Height is a key factor in a car’s deadliness for two main reasons: First, a taller vehicle is more likely to strike pedestrians in the torso or head, causing more serious injuries than the (also highly unpleasant) lower-body injuries caused by shorter cars. The second reason is nothing short of ridiculous. American SUVs and trucks, nominally designed for “utility,” have gotten so big that many of them have enormous blind spots right in front of the driver. A local news segment from Indiana went viral after reporters found that eight children can sit down in front of a Chevy Tahoe without the driver being aware of a single one, while the Tahoe’s cousin, the Cadillac Escalade, can fit a dozen children in its fifteen foot-long front blind zone.

Many enormous autos like the Hummer EV now feature cameras aimed at the front blind zone. Stop and think about that for a minute: As cars have gotten bigger, we’ve made it harder to see out of them, and our solution is a screen with a seeing-in-front-of-you app.

Sadly, electric SUVs and trucks pose a unique threat. Replacing combustion engines with batteries adds significant weight—often more than 1,000 extra pounds—while also making vehicles quieter and giving them quicker acceleration. That combination means that electric vehicles hit pedestrians with greater force than their predecessors, affording victims less warning and less time to react. The trademark whine that Teslas emit is not a byproduct of their engines, but rather a “pedestrian warning system” designed to mitigate the problem of silent cars sneaking up on people. This idea is genuinely good, and should be mandatory for all electric vehicles, but of course, since these cars are primarily toys, Tesla has also invented a way for drivers to cancel out these warnings with fart sounds and other funny noises.

What are we trying to accomplish here, exactly? Even if we accept that electric cars are better for the environment than fuel-burners (a question that gets complicated when we remember that more than half of America’s electricity still comes from fossil fuels), their rise has also led to a stark divergence between small, practical cars and the giant, goofy ones favored by American manufacturers. Any sensible government would immediately implement a coterie of new safety standards, including an outright ban on consumer vehicles capable of running over a dozen children before the driver notices they’re there. But in America, deadliness has never really been disqualifying when it comes to our favorite toys. So for the time being, there’s only one thing for pedestrians to do: Watch out!