On a recent walk through Brooklyn, I came upon five or six spotted lanternflies and stopped to stomp on as many as possible. A passerby congratulated me, and we chatted briefly about the best way to attack this invasive species. As we parted, she waved a friendly goodbye and wished me, “Happy killing!” At a time when so much divides us, murdering spotted lanternflies is bringing Americans together.

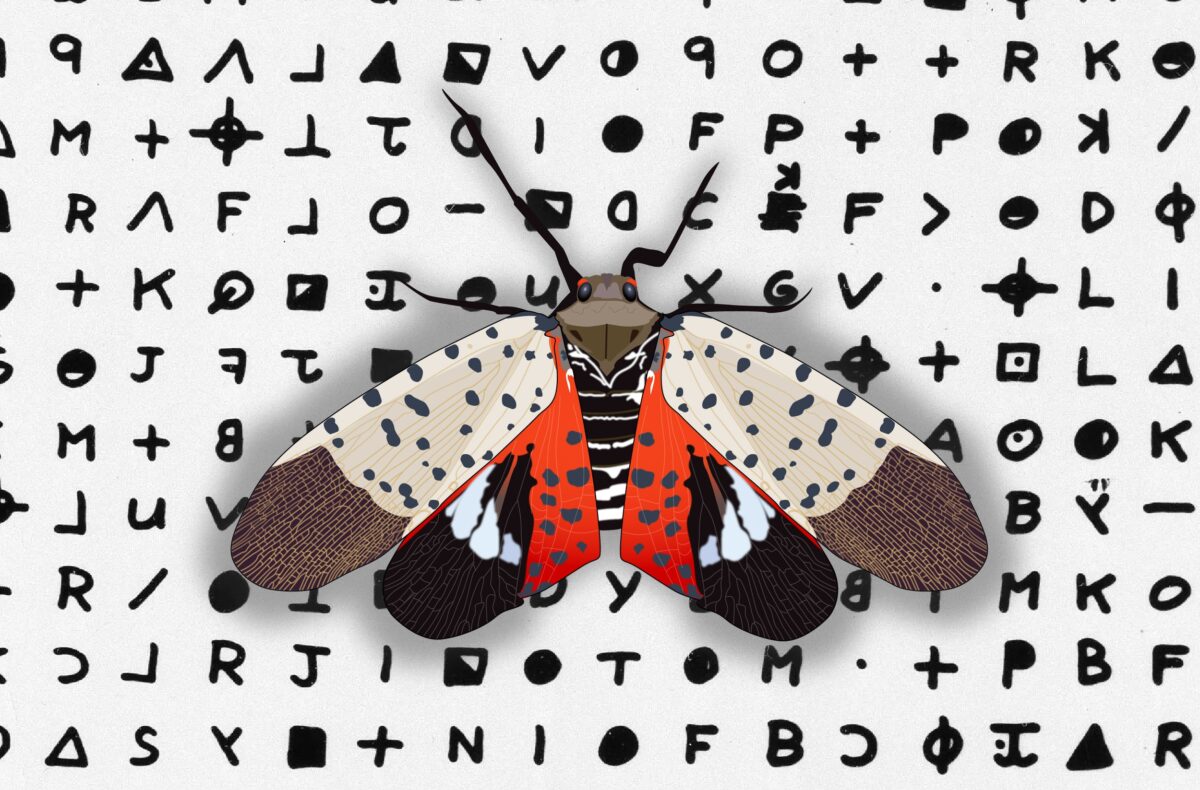

In recent years, scenes like this have been common up and down the East Coast, as officials issue the kind of orders one doesn’t typically expect from stewards of the environment: If you see a beautiful little bug with delicate, spotted wings sporting a brilliant shade of red, kill it at once.

Lycorma delicatula arrived here by accident. Sometime before 2014, a spotted lanternfly in China laid eggs on a shipment of stone, and that stone found its way to Berks County in central Pennsylvania. When the eggs hatched, the nymphs found themselves on a new continent, one with a smorgasbord of feeding opportunities and no predators specialized in hunting them—except for homo sapiens.

“It was a case of building the plane as we fly it,” said entomologist Heather Leach of Pennsylvania’s response to the lanternfly. Currently an orchard manager at Cherry Bay Orchards in Michigan, Leach spent several years studying the bug with the Penn State Extension. “All of a sudden we have thousands of these insects feeding on a single tree, and we know nothing about its biology.”

Before it became Public Enemy Number One, the spotted lanternfly was known chiefly to American scientists as an evolutionary oddity, part of a quirky family of insects that also includes the peanut-headed bug.

“This is one weird insect,” said Dr. Amy Korman of the Penn State Extension, an educational outreach institution that led Pennsylvania’s lanternfly response. “We just don’t know very much about it—and we know a lot more now than we did several years ago.”

What we have learned may be key to getting the situation under control: The spotted lanternfly has three digestive organs, each of which contains unique bacteria that are found nowhere else on Earth. These bacteria allow lycorma delicatula to feed on the sap of grape plants and a wide variety of North America flora. This makes the lanternfly a direct threat to many cash crops, but may also be its undoing, as researchers look for a way to neutralize these bacteria, which would make it impossible for the bug to feed.

Despite being a mediocre flier and a lazy breeder, with just one generation per year, the spotted lanternfly is adept at multiplying and spreading. Dr. Mark Hoddle, a biological control specialist at the University of California, Riverside, explained that, while many insects only lay their eggs on specific parts of specific plants, the spotted lanternfly lays eggs “indiscriminately.”

“The difficulty comes from managing vast areas that the lanternfly can get into,” Hoddle said. “I’ve seen photos of eggs on rocks and on picnic tables, on people’s barbecues, and on the sides of rail carriages that get transported across the country.”

That characteristic has made it very hard for authorities to contain the threat. Pennsylvania has “quarantined” many counties, making distributors and business owners there undergo training to detect the bug and stop it from spreading, but the lanternfly has still managed to flourish. From the first sighting in Pennsylvania, the bugs have made it to at least 13 other states, from Massachusetts to Indiana, their numbers increasing every summer.

As the lanternfly spread and officials urged the public to kill as many as possible, the public leapt into action. But for every well-intentioned “Lanternfly Murder Pub Crawl,” there was a homeowner who mistook weed killer for pesticide, and ended up destroying the plants they thought they were saving. Leach recalls some Pennsylvanians setting backyard trees on fire in misguided attempts to get rid of the pests. She now wonders if the threat was properly communicated.

“The biggest thing for us has been understanding impact and who’s at risk,” she said. “What I found is that the risk was kind of overstated for spotted lanternfly damage to pretty much all agricultural crops [in Pennsylvania], with the exception of grapes.”

The Penn State Extension has developed a handy guide to lanternfly management that instructs the reader on the difference between a low-risk situation (like seeing one or two lanternflies on a tree that isn’t threatened) and a true cause for alarm (like finding an army of lanternflies adjacent to an orchard). Korman recommends against the “nuclear option,” severe pesticides, in cases where the danger is low. Instead, concerned citizens can make circle traps, scrape egg masses into containers of hand sanitizer or rubbing alcohol, or, of course, simply squash them.

“It’s actually a very fragile insect,” she said, recounting instances where lanternflies have been observed climbing up buildings, simply to fall off and perish. “Look at it cross-eyed, it falls over and dies.”

Nevertheless, farmers and biologists are bracing for the moment when live lanternflies finally make it to the West Coast.

“We were able to piggyback pretty quickly onto some of the programs that were already being developed on the East Coast,” Huddle said. His lab and others across California have received grants from the U.S. Department of Agriculture, funding research that could make life difficult for lycorma delicatula when it inevitably arrives there. With help from the USDA, Hoddle is working with tiny insects, called parasitoids, that lay their eggs inside of lanternfly eggs.

“Instead of getting a spotted lanternfly hatching out of that egg, you get a parasitoid that emerges,” Hoddle said. “And its focus is to look for more spotted lanternflies to attack. What’s nice about this situation is, if you can find effective and environmentally-safe parasitoids…you don’t have to be in what we call an ‘insecticide treadmill program,’ where you’re constantly spraying to control those pests.”

If this approach reminds you of another famous response to an invasive species, well, that makes two of us. Hoddle assured me that no parasitoids will be introduced into the wild until scientists are certain that only lanternflies will suffer.

Between general predators, old-fashioned pesticides, and innovative approaches like parasitoids and targeting gut bacteria, entomologists are confident that we’re on our way to an equilibrium. If governments do their job, affected business owners will receive the assistance they need to weather the invasion, and the lanternfly will join the ranks of controlled pests. No amount of stomping will eradicate the bug from this continent—it’s just one of many ecological problems we’ve brought on ourselves.

“Human enterprise, whether it’s trade, tourism, or agriculture, has accelerated these problems that we are now facing,” Hoddle said. “And as the climate changes, it’s creating opportunities for new types of bugs to come to areas that may have previously been inhospitable to them.”

Hoddle praised the USDA, saying he hoped that Americans understood the benefit of funding research into invasive species. “A lot of people don’t realize what we’re up to,” he said, “but that’s what their tax dollars are going to. This is public-good work.”

Leach called for better funding for port authorities and early-detection programs, in the hope of catching more invasive species before they can get loose. She also thanked the people of Pennsylvania for forcing their politicians to take action against the spotted lanternfly.

“They really started to reach out to their local legislators,” she said. “When private citizens ask what they can do, a huge part of that is writing to their legislators and trying to fund efforts, not only for spotted lantern fly, but also for other invasive species.”

The campaign to squish every lanternfly in North America may fail, but it’s encouraging to see Americans mobilizing on behalf of their environment. Though the spotted lanternfly is still an active threat, it may be best understood as a warning, a relatively benign example of a man-made environmental problem that necessitates a massive public response. With that in mind, a genuinely widespread movement to control the lanternfly and defend ourselves against the next invasion is a stomp in the right direction.