Everyone buys a story.

Tom’s. Fiji Water. Small Business Saturday. Buying American. Community sourced agriculture. “I used to be a plastic bottle.” Biodynamic wine. Microfinance. Pretty much everything on every shelf at Trader Joe’s. Sex sells, but the story gets you in the shop. What’s a product without a press release? The word “artisanal” haunts our commercial transactions like a hound from hell—or Portland. The backstory informs most levels of human consumption, from food to resumes to art.

Lives of the poets, lives of the saints, lifestyles of the rich and famous. Thank Plutarch. Thank Robin Leech. It starts innocently enough, and ends in a 3am Wikipedia rabbit hole. It begins, always, with a simple question: Who is that woman in the painting? Did he die writing his Requiem? When was the bus crash that put her in the body cast? In what West Village bar did he drink those 18 whiskeys? How old was he when he cut off his ear? Who was her husband when she stuck her head in the oven? Okay, maybe it doesn’t start innocently, but with a prurient, morbid fixation on sex and tragedy. Nevertheless, it is the stuff of Academy Award™ nominations and museum programming.

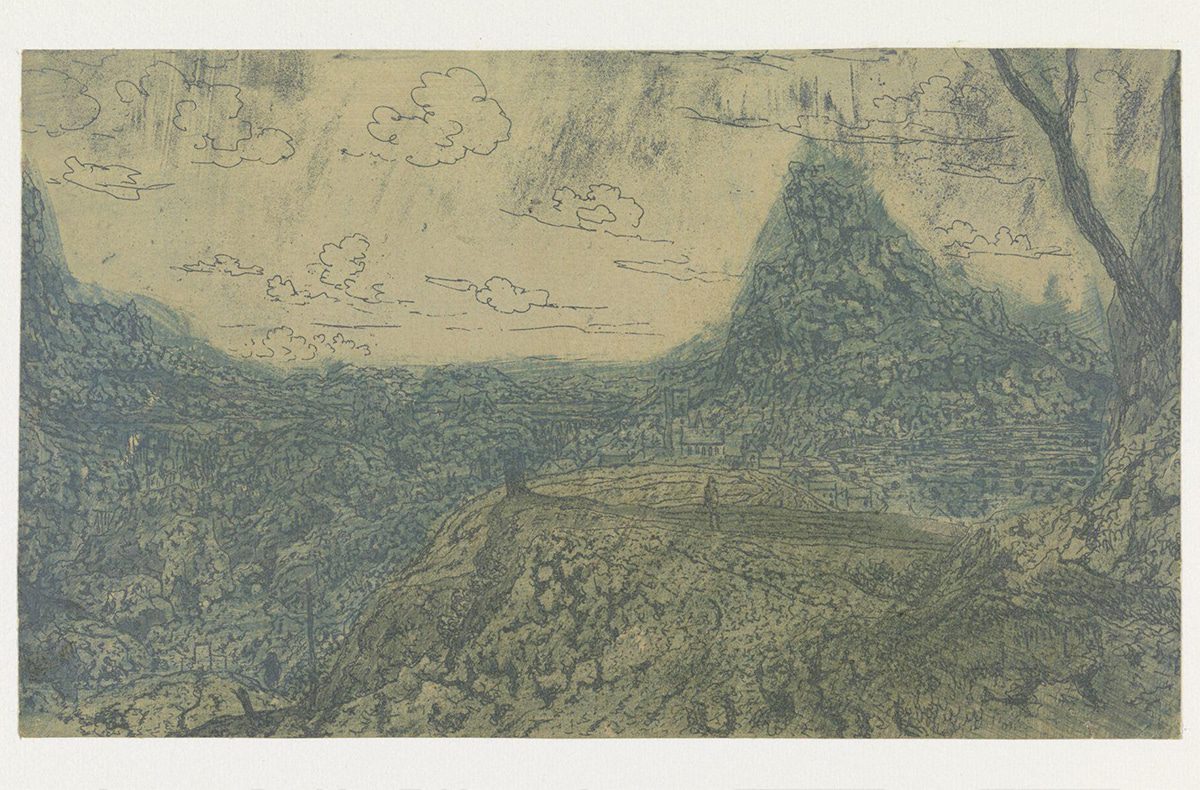

A few years back, there was a show at the Met called “Mysterious Landscapes.” It was a survey of an artist improbably named Hercules Segers, who was born in Holland in about 1589. He painted landscapes, tiny landscapes (which is weird enough when you think about it). He revolutionized printing as a medium and made strange use of color and perspective. Rembrandt revered him. But here’s the thing: he painted landscapes that look like Yosemite or the Amazon or Mars via a prog rock album cover—and he never traveled further than Brussels.

Folks, he made it all up! In the authentically sourced hell of the 21st century, the Met chose to feature a guy who just made shit up. How thrilling! And what’s more: we know almost nothing about him. Even the year he died is a mystery. Also—and this cannot be stressed enough—his name is phenomenal: Hercules Segers. (But because he’s Dutch, I have no idea how to pronounce it.) Rather than try to construct any sort of story for Hercules Segers, the curators seem pleased to let his preposterous name stand on its own. Oh, and his art. The curatorial content hails him as a “genius” and an “innovator” and almost delights in the fact that he left no biographical record for the last ten years of his earthly existence.

Unencumbered by the burden of having to wonder who will play Segers in the biopic (let alone pondering the inevitable decline and fall of whatever child actor lands the part of little Hercules), the curators have been set free! So they have written about radical technique, exciting new authentication, and a pure creative force that has slipped the surly bonds of biography to touch the face of a contemporary viewing audience. It’s one of the few times I can say I was truly in the room with the art, rather than its hype, backstory, aura, or price tag.

And, yet:

Whenever you see any kind of show, to talk to those who haven’t seen it yet, you go into the backstory—as I just did. You say whatever the museum told the weekly magazine you read to say about it. How is this any different? In fact, in our era of the never-ending, daily biographical arms race called social media, is maybe having no biography the ultimate status symbol? Is the total abnegation of biography the ultimate biography? Will the next step be not needing to do anything so tacky as tell the world who you are?

Well, I’m not holding my breath. On the one hand, it is so exhilarating to be in a room full of visions brilliantly unbound from the torture of facts; on the other, we remain so enthralled to the cult of personality that that the lack of source material for this remarkable (or unremarkable, but certainly unremarked upon) life is, in fact, the story. So still, we buy the story. If there could be a show about nothing, certainly there can be a life of the artist with no life at all.

When I was an undergraduate, I got into an argument with my creative writing professor, a famous poet who has since passed away. (I won’t keep you guessing: C. K. Williams.) Our assignment for the week had been to write a poem in the first person. I finished reading mine and my professor asked me when the events in the poem had happened to me.

I replied that they hadn’t.

According to him, all poetry is autobiography. This blew me away. He scoffed at me as the rest of the class shifted uncomfortably, recalling the poem he’d recently read to us about getting a handjob by the side of Route 1/9. Pretentiously, I retorted, “Did Dante go to hell?” And, reader, it shouldn’t surprise you to know that, unlike my professor, I have yet to win a National Book Award, or a Guggenheim Fellowship, or induction into the American Academy of Arts and Letters. So, I guess that was his retort. Nearly 20 years later, I still disagree. (Hey, the least a stubborn person can offer you is consistency.)

But there is a caveat: no, I don’t think all poetry is autobiography but I do think all poetry needs autobiography. Or, more accurately, the audience needs autobiography. They crave it, demand it, live for the shit, use it as a means to get closer to the art, to touch the gravestone, to connect. We demand total immersion when any kind of art or music or poetry speaks to us.

In short, we fall in love.

And, like lovers, we essentially delude ourselves. First, we delude ourselves that any other human is knowable to us. It is actually impossible to know the person next to you in bed, let alone a landscape artist who has been dead for nearly 500 years. (One whose ridiculous name you don’t even know how to pronounce.) We delude ourselves as to who these artists and writers and poets are. We literally place their likenesses on pedestals.

This pattern of delusion started with the saints, who were useful solely on the merits of biography. Their likenesses were also placed on pedestals. And what are artists, really, as we invoke them, other than secular saints? The French Revolution was prescient to disinter its intellectual heroes and gather their relics in the aptly named Panthéon. Our modern pantheon of intellectual heroes is ever-shifting and filled not with actual historical personages, but with our most useful versions of them. For instance: a rapping Alexander Hamilton with an abiding—and fictitious—passion for racial justice. Before him, it was an emotionally vulnerable John Adams. I cannot tell you what Founding Father will be next, or how we will dress him up, but I wait with baited breath.

We bend the biography, as we do with any objection of infatuation. And that act of bending tells you more about us than it ever will about the person portrayed in the musical or HBO series. Personally, I don’t see much that is problematic about this—so long as you acknowledge you’re leaving the real person out of it entirely. And no one does that. What would be the fun in appropriating a biography—riding that social-historical context off into the sunset—while dragging a fat disclaimer behind you? What would be the point?

Yet, I’d be lying if I said it bothered me much: historical interpretation is a sign of the times, a collection of stories we tell ourselves about how we got into this mess. And those stories, and the conversations we have around them, are important—maybe even the vital signs of shared civic life. They map out the cultural landscape.

No, the real problem comes when the person in question—or, should I say personage—isn’t dead yet, but inconveniently alive. And, even more inconveniently, still producing work. And, worse yet, that person is fucking up. Badly. Maybe the new work is no longer great. Maybe the meteoric ascent is just beginning. Maybe this artist has truly hit stride in a given medium. And maybe, just maybe, another party wronged by this eminent artist has aired grievances so wrenching, so humiliating, so weird, that, even if we don’t automatically believe every word off the bat, we understand one person is willing to ruin their own life to bring another to account.

An artist has the resources of both art and biography to tell a story. Everyone else only has biography, meaning in all likelihood this accuser has temporarily—or permanently—given over their ONE shot at a storyline to this accusation. Their portrait will be lit, harshly, by this single source of light, all in the hope that they can maybe do the same to the accused’s.

I am a natural skeptic. I am a believer in due process. But, before either of those things, I am a storyteller. I do not wonder so much about the biography of the accused, so much as that of the accuser, who has now surrendered their story entirely to this one thing, to the very object of her hate, to this force of destruction. That, I think—more than being a woman or raised a feminist—is why I always listen to anyone willing to go public with an accusation.

Going public means laying it all bare: one’s political affiliations, one’s past, one’s place of work, you name it. This process is brutal. It is unfair. It doubly wounds those who have already been wronged. The fantasy may be that of a liberator, tearing down the tyrant’s statue; the reality may end up more like a spiteful moon doomed to orbit the Great Man for eternity—or until it is pulled in by gravity and comes crashing to the surface in fiery, self-destructive, cratering dive. No matter what, the process is tremendously unpleasant, and anyone willing to go through it has earned at least a hearing, in my book.

So, let’s say they get their hearing. Let’s say they had been wronged but that, against all odds, the system works. Punishment is meted out and they are vindicated. Let’s tack on a happy ending and say they can move on with their life—even though the cruelest irony yet is that the greater the wrong and the more famous the man, the more it will stick to them forever…But let’s say they move on, and out of this essay.

What’s left?

Do we knock the secular saint off the pedestal for ceasing to be useful or for having a biography that got in the way? Though such reckonings are usually romantic in nature—or, at least sexual—the spurned lover in this scenario is, in fact, the adoring public. The object of our obsessions, our infatuation, our love, has betrayed us, or at least turned out to be an asshole. We are wounded; we cry foul! Our hearts are broken and, outraged, we seek to heap scorn, throw all the bastard’s earthly belongings out on the curb. Except, in this case, it’s not clothing or shitty vinyl going out the window, but rather an entire body of work.

Here we may pause and note that all’s fair in love and war. But all is unfair in art. This starts with who is blessed with talent in the first place—and the access to bring it before a public, and the education to polish it, and the timing for it to resonate, and the critical reception for it to stick, and the venue that flatters it, and the stable home life to nurture it, and the health to carry on creating…The list is unending, as are its variants for various points in time.

Can we dismiss the biographies of artists who happen to be terrible people? Do artists need to be good to be great? As I’ve noted in my writing before, I was raised by a Jew who adored Wagner. The feat of separating art from artist is Herculean—which is possibly an indication of how Segers pulled it off. We need to ask these questions not just because of cancel culture, but because we have more access to all of this information—and more ability to contribute to the cultural conversation—now more than ever. Biography is no longer left to the hagiographers and Vasaris among us: rather, social media and the never-ending news cycle have produced an ongoing narrative we follow in real time. There is even the illusion of participation as we comment, troll, repost, and react.

Some will say that participation is not an illusion. While I’m tempted to agree—the pressures of social media are very real, and, even before social media existed, the lone nut always had the chance to intervene, or even terminate the life of any artist—we, the public, only enter the finished biography. You can out Dustin Hoffman as a pervert on social media; you can even shoot Andy Warhol, but that doesn’t mean you starred in The Graduate or had anything to do with the electric chair paintings.

The work alone has never been enough: such is the nature of love that we need to like the person and not just the inestimable cultural and artistic contributions they have made to our lives. We feel this way about food, too, about everything “ethically sourced.” Maybe it’s not love, after all, but simply consumer choice. That notion of agency is critical. First we need to remember that stories are just that: stories. We choose what to tell ourselves about what we consume. Mainly we tell ourselves these stories to feel better about our choices. One symptom of capitalism is consumer expiation.

The consumer of art in 2022 needs a new relationship to the moral price tag of any cultural artifact. Step one: DO NOT LOOK AT THE BACK STORY. Fall in love with the song, the movie, the book, the painting before you do anything else. Pretend the biography does not exist. Only and only if you have fallen in love and decided this thing is a part of the fabric of your imagination do you need to look at the moral and ethical price you will pay for loving it and making it yours. At that point, come hell or high water, you will pay that price. You will figure out how to get the capital, scrounge around, and—in the process—both educate yourself as a consumer of culture and as an independent person of free will and moral agency who can wade into the complexity of human life and understand that good things often come from terrible places. And, moreover, that this is more than okay—it’s redemptive.

The effort involved in meaningful cultural conversation, open discussions of prejudice, self-examination, empathy for those hurt by makers of things you love, and the overall work around keeping an open mind is, indeed, Herculean.