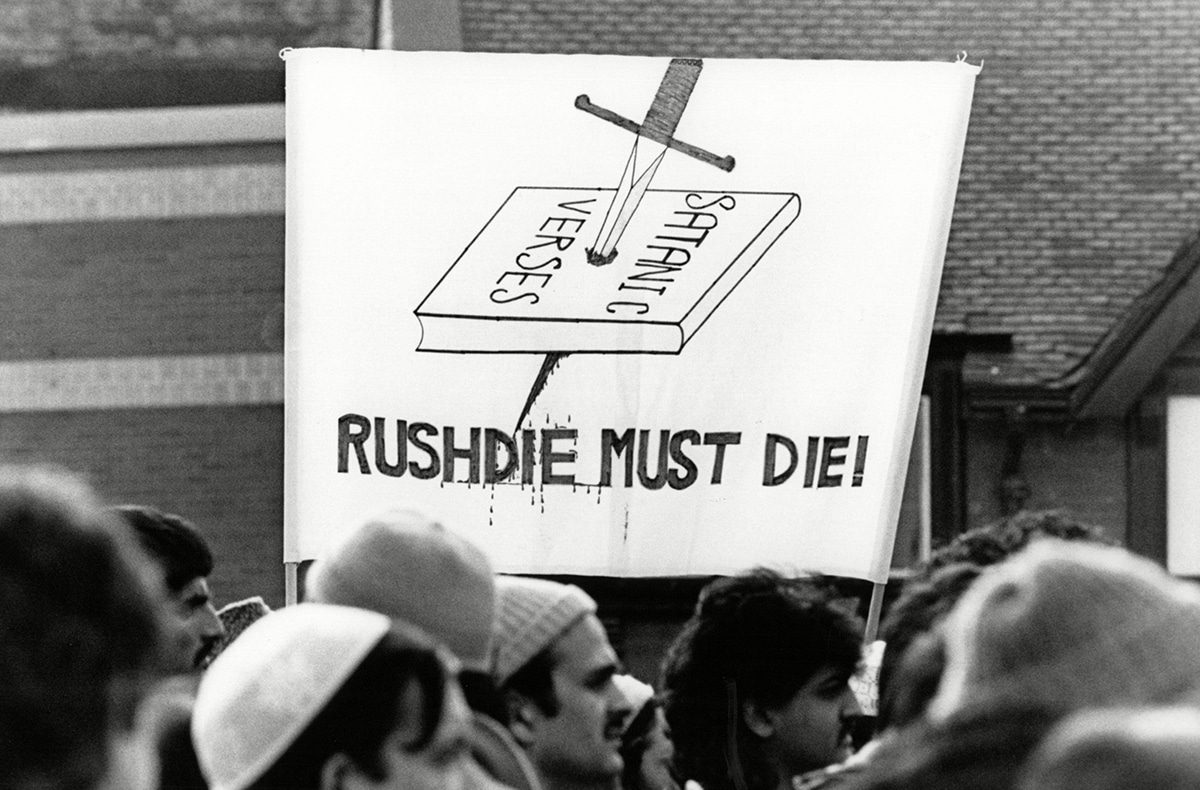

The stabbing in New York State of author Salman Rushdie, at the hands of New Jersey-based Hadi Matar, is a gory reminder of how dissenters of Islam continue to be vulnerable to violence around the globe, including the US. Put on a hitlist after fatwas across the Muslim world for the past 33 years over The Satanic Verses—which used allegory and satire on Islam in a magical realist narration on migration to England from the Indian subcontinent—Rushdie has been the most high-profile target of those that have codified death and violence for offending Islam in Muslim-majority countries.

Codification of gory blasphemy laws in the Muslim countries stems from Islamic jurisprudence. Even the most generous interpretation of Islamic sharia would limit it to medieval law that was, at best, suited for the times of early Islamic empires. Today these antediluvian blasphemy clauses, including upholding capital punishment for criticising Islam, are etched in modern day Muslim constitutions that also simultaneously aspire to safeguard freedoms of speech, conscience, and religion. This paradox is rooted in the failure to grasp “freedom” itself: that freedom of religion is also from religion; that freedom of conscience means room to disparage the holiest; that freedom of speech doesn’t exist without the freedom to mock.

Ideologies that the majority adheres to, beliefs that are widely accepted, and expressions that are largely endorsed, do not need any legal shielding. It is precisely those ideas that fall on the spectrum that ranges from dislike to outrage that need the protection from any fear of violent retribution. Ideologies do not, and cannot, have rights that have been designed to ensure liberties of humans, as long as they do not seek to deny another’s rights. For, this cannot be applied to beliefs, given that competing ideas are intrinsically offensive to one another, resulting in the impossibility—not to mention the jurisprudential depravity—of a right to “not be offended.”

It is only those expressions that seek to infringe on the rights of individuals or communities, including explicit incitement of violence, that should be sanctioned by penal codes that are uncompromisingly egalitarian, which the majoritarian Islamic laws are not. However, as the precipitously escalating cancel culture delineates, it is not merely Islamists that fail to grasp freedom to offend as the raison d’être for freedom of expression—even if their assault on free speech continues to be its most literal, and most gruesome, rendition.

Where Islamists are declaring dissidents of Islam, such as Rushdie, wajib-ul-qatal (liable to be murdered), sceptics of a new wokeist dogma are now being deemed wajib-ul-cancel (liable to be cancelled) for questioning particular ideas. Some like Richard Dawkins and Ayaan Hirsi Ali have had the honour of being labelled both. Rushdie—especially his staunch defence of free speech—too was abandoned by the progressive circles in the West. It is no coincidence that threats for JK Rowling—despite her longstanding dedication for protection of Muslims against anti-Muslim bigotry—came amidst news of the stabbing on Rushdie, given how wokeist mobs have dehumanised the Harry Potter author over her vocal disagreement with the far-left gender ideology.

Both the Islamist and wokeist ideologues also have a tendency of letting their respective uncompromising dogmas erode their own circles, with Islamic excommunication of other Muslims being reciprocated by virtual apostatising of progressive thinkers, which is devouring the global left. Just as one can never be “Muslim enough” for Islamists, one can never be “woke enough” for the loudest proponents of cancel culture, a natural corollary of puritanic groupthink empowering the propagators of the narrowest version of the ideology.

Those who find comparisons between Islamism and wokeism hyperbolic, should remember how much of the discussion in the US over the Chris Rock-Will Smith episode in the aftermath of the Oscars in March was over how the comic’s jokes had “punched down,” even when he had been actually and physically punched with millions watching worldwide. This was no different to how Charlie Hebdo, which has satirised other religions—especially the Catholic church—significantly more than Islam, was derided for treating Islam the same as any other ideology, in the aftermath of the French satirical publication witnessing its journalists being massacred by offended individuals. Apparently, it is asking too much of even those who self-identify as “progressive” to agree on the fact that simply no expression—spoken, written, or illustrated—merits physical assault, under any circumstances whatsoever, no matter the magnitude of caused offense or decibels of intangible hurt.

This catastrophic failure of even the so called “free world” to stand by the founding principle of liberalism—the uncompromising defence of the right to make choices that one, or others, might not approve of—is especially revolting for those of us in parts of the world that actually codify death for certain expressions. Those who claim “words are violence” are unlikely to have lived under the shadow of actual violence, especially the kind sanctioned in response to dissenting words.

Rushdie, of course, has lived over three decades under a global death threat. Condemning the attack on him, and supporting free speech, is incomplete without individual and collective efforts to safeguard the freedom to offend. For, it is today under attack at the hands of both religionist and progressive absolutists.