This project is an appraisal of the world that was wished upon us.

Twenty-five years apart, in the very heart of the American Century, two World’s Fairs were held in Flushing Meadows. On the precipice of World War and at the height of the Cold War, the world came to New York City, and New York City showed itself to the world. Tens of millions of visitors flocked to Queens to glimpse the American Way, paved the world over as an unyielding, uniform path hewn by capitalism and democracy. They stood in awe before the Unisphere and beheld the unilateral force that thundered forth as mushroom clouds—and Coca-Cola.

The World’s Fairs are a testament to a time and a place when America looked both within and without, from a city that dares to call itself the Capital of the World. Through a sensibility that emphasizes intersectionality, interconnectedness, and correlation, I Have Seen the Future takes the opportunity to look back at how visions of utopia of 1939 and 1964 have defined our reality in the 21st century. Named for the slogan on pins that were available at General Motors’ “Futurama” in both 1939 and 1964, I Have Seen the Future is a multifaceted, immersive exhibit of components meant to evoke the experience of visiting the World’s Fair—with the hindsight of 2022.

In truth, the project leans more heavily on 1964, which was a World’s Fair not sanctioned by the international governing body, and therefore reliant on corporate funds. That private-public partnership feels very familiar in 2022. With an eye on continuity, the work asks how the Space Race was not just a proxy for the Cold War, but for WWII, and a conflict that arguably is ongoing; it examines utopia as a violence that enforces segregation in myriad ways that define wealth and income distribution in America; it shows how state surveillance harassed and even assassinated civil rights leaders to protect social order.

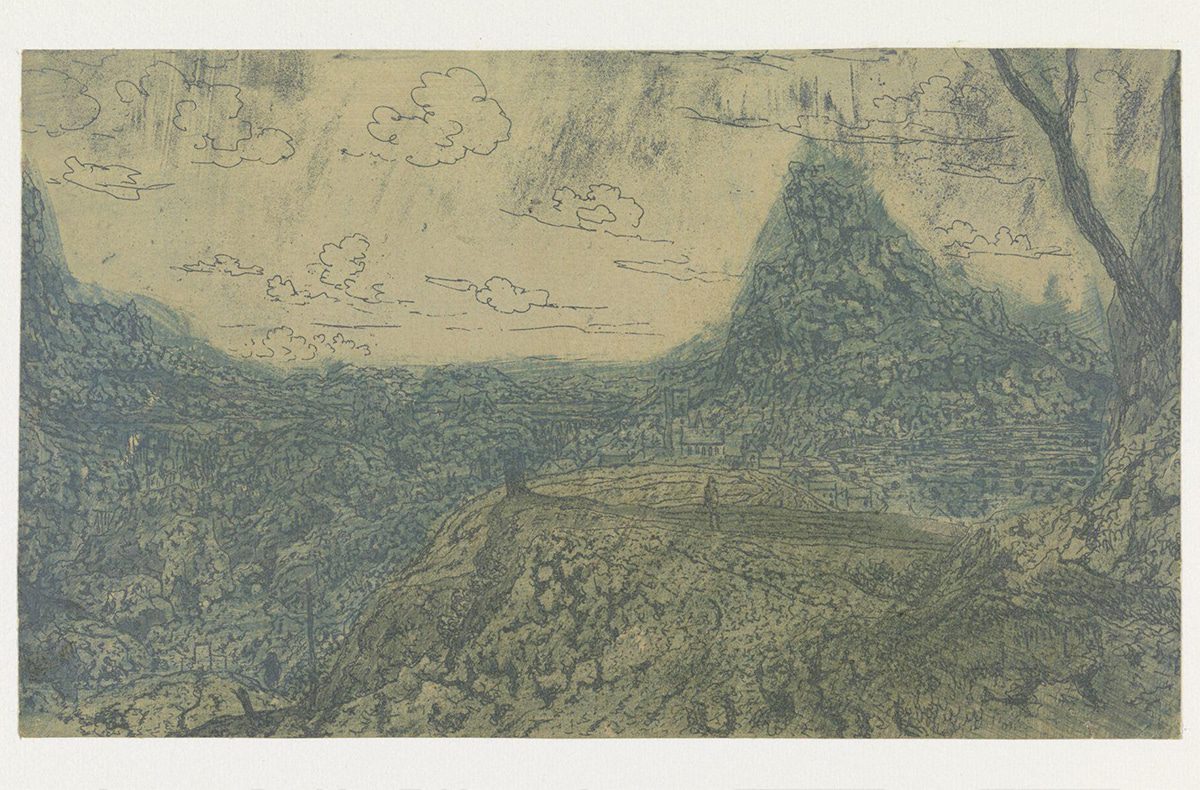

Johannah Herr’s flocked architectural models are sculptural objects that each represent an imaginary pavilion in a themed “Area” of the World’s Fair. The display is also accompanied by patterned, flocked wallpaper that references 1960s interior design and subtly contains language of racially restrictive covenants in postwar housing. These are complemented by a digitally printed “Ironic Curtain” detailing unfortunate Cold War-era parallels between the US and the USSR. Naturally, the floor is tiled in linoleum; the entire exhibit is rendered in a late 1950s palette reminiscent of the era’s appliances—which were decidedly weapons in the Cold War.

The seven models have been photographed and included in I Have Seen the Future: Official Guide, a collaboration I wrote with Johannah that expands upon the themes tackled in the models through text and subverted advertisements. Through these items, we emphasize a worldview that hinges on interdependency—a concept all too foreign to the country that gave the world the cowboy, the pioneer, the action hero.

Together, we look at the world we inherited, again we look at it from New York. We glimpse the panorama. We see the moment that the war came home erased from history where twice we modeled utopia in Queens. Once more, we watch a land war in Europe with economic crashes and a global pandemic in recent memory. New York may well be the world’s capital and it welcomes the world, but it also is the largest city in a country that stubbornly refuses to understand a contemporary world that it has done more than any other existing nation to shape. Once more, we have a Space Race, but, continuing the trajectory of the World’s Fairs, it has cooled from a proxy war in the name of progress to a tepid 15-minute joy ride for oligarchs in a phallic cocoon. The Cold War is often described as a backdrop but it sure has a talent for coming to the fore over and over, a sort of multigenerational landscape.

We also revisit the legacy of Robert Moses, whose iron grip on New York was bookended by both World’s Fairs in Queens. In Moses’ impact, we see the violence of utopia and the violence of urban planning when coupled with virulent, unrepentant racism. Asking “Who is Robert Moses?” feels an awful lot like asking, “Who is John Galt?” The notion of a Galt gone awry perhaps tracks, not that Galt had a hope of going a-right in the first place—unless you mean ideologically. Imagine: a Republican (or anyone) invested in public works! Except, he wasn’t of course. Rather, he enriched himself through a larcenous public-private partnership at once at the geographical heart of New York City, yet nearly invisible to all: directly beneath the Triborough Bridge. (That bridge is now renamed for Bobby Kennedy who—as is explained in the book—both wiretapped Martin Luther King, Jr. and served as an aide to Sen. Joseph McCarthy.) All of these legacies collide and collude as we appraise how we go to 2022.

Starting tomorrow, we hope you might peruse the pavilions of the tomorrow that was yesterday, and take a moment to read a word form its (many) sponsors! Through these objects, we invite you to behold the future we were told to hope for.

I Have Seen the Future will be on display at Field Projects in Chelsea, New York City from April 7 – May14. Advance copies of the guide may be purchased here.